Archive : Article / Volume 2, Issue 1

- Research Article | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-2179/012

The application and evaluation of an augmented-reality-based physical and cognitive stimulation programme for older adults

- University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

Catalina Guerrero-Romera

Catalina Guerrero-Romera, PabloAvilés-MartÃnez, MarÃa del Carmen GarcÃa-Collado (2023), The application and evaluation of an augmented-reality-based physical and cognitive stimulation programme for older adults. Journal of Emergency and Nursing Management 2(1). DOI: 10.58489/2836-2179/012.

© 2023 Catalina Guerrero-Romera, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 24-02-2023

- Accepted Date: 17-03-2023

- Published Date: 27-03-2023

active ageing; healthy ageing; older adults; cognitive processes; assessment and intervention; technology and virtual or augmented reality

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to present the results of research analysing the incorporation of virtual or augmented reality into a programme based on physical and cognitive stimulation in older adults and to evaluate its effects following its application. The specific objectives were to verify whether the intervention had a positive effect on the cognitive deterioration of older adults as far as their mobility and fall risk were concerned and whether it was possible to observe any significant differences. A total of 18 people over the age of 65, all of whom were users of a day centre for the elderly, participated in this research. In terms of methodology, the study employed a quasi-experimental approach with two groups and both a pretest and a posttest to analyse the data quantitatively and descriptively. Three scales adapted to a Spanish population were used to measure cognitive deterioration, mobility and fall risk and to evaluate mental disorders in old age. As far as the results are concerned, although no statistically significant data have been found, it has been possible to appreciate slight improvements which suggest that virtual or augmented reality is a tool which can be used to complement physical and cognitive intervention programmes and activities in day centres for the elderly, incorporating aspects of an interactive nature which allow people to exercise and recover basic abilities in their everyday life, particularly in the area of cognition.

1. Introduction

One of the most significant advances made on a demographic level in recent times has been an increase in life expectancy. As a result, how to care for and attend the needs of people over the age of 65 is one of the greatest challenges facing society today and, in the future, along with the need for high quality professionalisation in terms of assistance for this population and the importance of applying new models of care, adapted to the profiles and needs of older people. Fostering healthy ageing is, therefore, essential for the implementation of great global agreements, such as the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021-2030) announced by the General Assembly of the United Nations, demanding “concerted, catalysing and collaborative actions in order to improve the lives of older adults, their families and the communities in which they live” (ONU, 2020, p.3).

Furthermore, the 2012 report on dementia of the World Health Organisation estimated a global prevalence of 35.6 million people with dementia and calculated that this number would double by 2030 and triple by 2050 (McEwen et al., 2014). The objective of cognitive rehabilitation is to directly confront the most relevant cognitive difficulties for the individual and his/her family members (or carers), as well as to become aware of and provide guidance for the everyday challenges of his/her life (Bahar-Fuchs, Claire & Woods, 2013),

As people get older, they suffer an increase in the incidence of cognitive and neurological deterioration. While the processes considered to be the result of normal ageing lead to an irregular decrease in the speed and of cognitive processing and movement (Christensen, 2001), the most common neurological and cognitive disorders among older people lead to a loss of specific functions, be they basic neurological functions (memory, attention and perception) or executive functions (organisation, planning and problem-solving) (Riddle, 2007).

Within virtual environments, it is possible to systematically plan tasks aimed at cognitive performance and to introduce tools which make it possible to reach beyond the essential aspects which define the use of traditional methods. This implies the opportunity to develop innovative tools for neuropsychological evaluation and recovery via the development of scenarios and activities which would be extremely difficult, or even impossible, to achieve by way of conventional neuropsychological methods. The challenge, as stated by different international organisations, is to foster active and healthy ageing, thus enabling us to make the most of the advantages and possibilities offered by digital technology in social services and in the health system.

From this point of view, virtual reality can be defined as an approach to the user-computer interface implying the simulation in real time of an environment, scenario or activity which makes it possible for the user to interact via different sensory channels. This may vary between non-immersive and a completely immersive modalities, depending on the degree to which the person is isolated from the physical environment when he/she is interacting with the virtual environment.

These characteristics have led to the development of a significant amount of research on the use of such tools as a means of exposure for the treatment of phobias or for the promotion of independence, with the effectiveness of this technique having been demonstrated in a number of studies (Botella, Fernández-Álvarez, Guillén, García-Palacios & Baños, 2017; Maples-Keller, Yasinski, Manjin & Rothbaum, 2017; Vega-García, Camacho-Lazarraga & Caraballo-Vidal, 2018; North, North & Coble, 2015).

Until the present, the development of the technology had not made it possible to carry out an in-depth exploration of this field, which presents a plethora of advantages for older people. However, virtual reality, like other technology, has proven to be an effective, motivating and safe training tool when used alone or as a complementary tool in conventional mechanisms for recovery (McEwen et al., 2014).

This paper presents the results of an intervention programme based on physical and cognitive stimulation for older adults and shows how the incorporation of virtual reality can benefit different user profiles. The specific objectives were to verify whether the intervention has a positive effect on both the cognitive deterioration of older adults and on their mobility and fall risk and whether any significant differences were found.

The design of the intervention consisted of three modules carried out in a room specifically built and equipped for this purpose. The room contained the following equipment:

- Virtual reality glasses: Oculus Quest 2 glasses, which project videos of significant places or moments for the users whilst interaction is generated with the therapist. This includes a regulated protocol of items to obtain quantitative values of this process. Duration: approximately 10 minutes.

- Movement sensor: Using a Microsoft Kinect device, exercises guided by a physiotherapist are carried out in which the users work on joint movement, walking and balance. Duration: approximately 10 minutes.

- Cognitive stimulation: Different cognitive domains are exercised (language, calculation, orientation, attention, memory, etc.) via a touchscreen device. Duration: approximately 10 minutes.

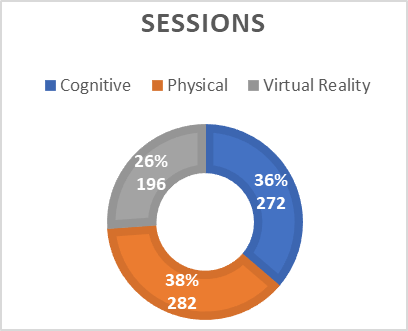

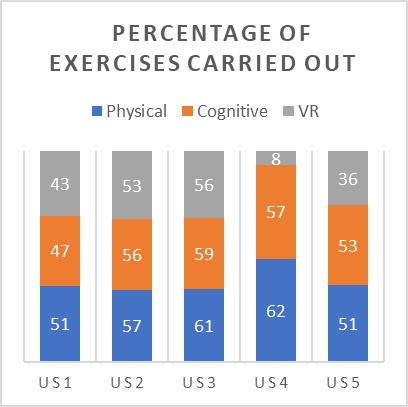

The intervention took place over a six-month period (24 weeks), during which the participants in the experimental group received three weekly sessions of 30 minutes each. The total number of sessions of the individualised intervention was 72 and a total of 750 exercises were carried out, the categories of which are itemised in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows a breakdown of the percentages of exercises carried out. As all of the participants in the control and experimental groups were users of a day centre for the elderly, the intervention took place in parallel with the routine activities of the services provided in the centre (guided physical activities in the gymnasium, cognitive stimulation groups, recreational activities, etc.). Thus, all future comparisons will be made based on a “usual” intervention in a centre of these characteristics and not with an absence of treatment.

Figure 1. Sessions

Figure 2. Percentage of exercises carried out

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 18 users of a day centre attended by 65 dependent older adults over the age of 65, participated in this study. They were separated into two groups. The first group was made up of 10 people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and moderate and severe cognitive deterioration, whereas the participants in the second group were not diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and had only slight cognitive deterioration (Table 1). In turn, the first group was subdivided into two smaller groups; one experimental group, consisting of five people who would receive the specifically designed intervention and a control group made up of five people who would carry out the routine activities of the day centre. The selected sample was divided due to the fact that there were people with severe neurocognitive disorders and others without neurodegenerative pathologies. The sample of people with Alzheimer’s disease could not be larger as other users of the centre with this diagnosis presented a level of deterioration which was incompatible with the intervention. The groups were counterbalanced in age (p = 1.000), cognitive capacity (p = 0.239) and physical capacity (p = 0.260). No significant differences were found between the means before the intervention was begun. The research was carried out after obtaining informed consent in the centre and respecting the confidential nature of the data obtained in accordance with the current legislation including personal data protection laws.

Table 1. Participants according to sex and age

| Older adults with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease | Older adults without a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease |

Sex | M= 3 (30%) F= 7 (70%) | M= 6 (80%) F= 2 (20%) |

Mean age | 81.4 years | 81 years |

Source: authors’ own elaboration

2.2. Research approach and data collection tool

The present study employed a quasi-experimental approach with both a pretest and a posttest, which were quantitative and descriptive in nature. The scales employed were the following standardised psychometric tests without modification. They have been amply validated and are widely-used in clinical contexts:

- Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Folstein test adapted to a Spanish population. This is a test for measuring cognition impairment, giving a quantitative score of between 0 and 30, with 0 denoting total cognitive impairment and 30 demonstrating a lack of impairment (Arévalo-Rodríguez et al., 2015).

- Time up and go. This test is indicated to evaluate mobility and fall risk among older adults. It consists of a circuit which must be completed by the user in the fastest possible time. A result measured in seconds is obtained which makes it possible to evaluate the user’s fall risk: less than 10 seconds indicates low risk; 10-20 seconds indicates medium risk; more than 20 seconds indicates a high level of risk.

- CAMCOG. This is a subscale of the Cambridge Examination for Mental Disorders of the Elderly (CAMDEX). It consists of 60 items associated to the main neuropsychological areas. The highest possible score is 133 points.

2.4. Procedure and data analysis

The data analysis was carried out with Mplus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) and the SPSS 24 data analysis program.

3. Results

3. Results

3.1. Analysis Group 1- Older adults with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease

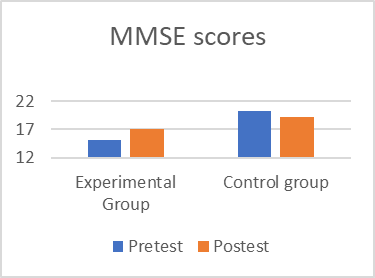

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the cognitive deterioration of the two groups in the different periods of evaluation. The 10 users ended the study without incident or periods of prolonged abandonment, with the exception of an individual session here or there.

Figure 3. MMSE scores

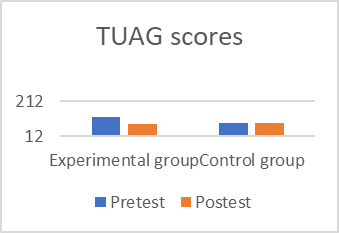

Figure 4 shows the evolution of physical parameters such as balance and walking evaluated in the different periods of the intervention. No incidents were reported and it was possible to evaluate all of the users correctly.

Figure 4. TUAG scores

These results show an improvement in the data of the experimental group between the pretest and the posttest. In the case of the scores obtained in the MMSE test, the mean score increased from 15.2 to 17 points, whereas in the control group during the same period the mean score decreased from 20.2 to 19.2 points as the participants’ cognitive performance reduced slightly. As far as walking and balance are concerned, the experimental group took, on average, 119.58 seconds to complete the test in the pretest, decreasing to 81.14 seconds in the posttest. The control group, on the other hand, began with an average of 85.42 seconds and obtained a score of 86.83 seconds in the posttest, demonstrating almost total stability throughout the duration of the study. However, these differences were not significant for the measurements of cognitive deterioration (p=0.195) or for the measurements of walking and balance (p= 0.065). The fact that the improvements cannot be considered to be statistically significant may be due to the study’s small sample size.

3.2 Results Group 2- Older adults without a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease

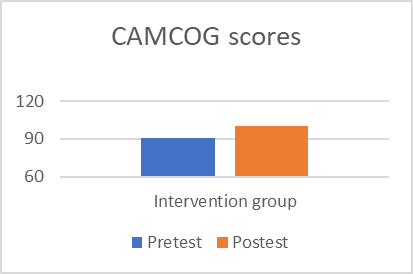

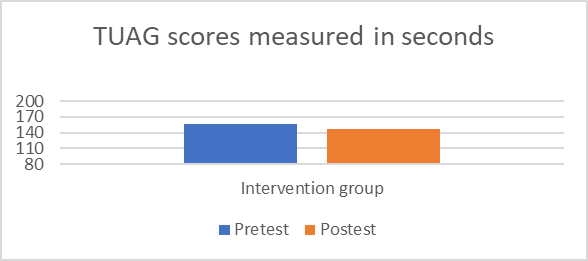

In this case, the intervention was carried out with only one group in the absence of a control group. Figures 5 and 6 show the results of the pretest and posttest, demonstrating the improvement in each case following the intervention.

Figure 5. CAMCOG scores

Figure 6- TUAG scores

In the case of the scores obtained in the CAMCOG test, the mean score increased from 91.12 to 100.6 points, whereas in the TUAG test there was an improvement from 19.5 to 18.4 seconds, taking into account, in the latter case, that a lower score is valued more positively (Table 2).

Table 2- CAMCOG and TUAG scores

| Average CAMCOG pretest | Average CAMCOG posttest | Average TUAG pretest | Average TUAG posttest |

Intervention group | 91.12 | 100.6 | 19.5 | 18.4 |

Source: authors’ own elaboration

4. Discussion and conclusions

The results obtained show a positive trend in favour of the use of individualised intervention and of virtual reality as a tool which complements standard programmes and activities relating to physical and cognitive intervention in centres for older adults. A slight improvement was observed in both cognitive performance and in walking and balance ability and all that this implies in terms of mobility and fall risk. However, the small sample size (as mentioned above), the impossibility of including male subjects in the control group and the difficulty experienced in establishing an appropriate intensity and frequency for the intervention (there are no data to compare whether longer or more frequent sessions would obtain better results) imply that all of the data is to be treated with extreme caution. As far as future lines of research are concerned, it would be of interest to apply a study which includes a larger sample size and completely randomised groups. It would also be interesting to add a third group including people who do not receive the intervention and/or do not attend a day centre. Another point of interest could be the inclusion in the analysis of the perspective of gender.

Different studies on cognitive rehabilitation have shown, with extremely positive results, the advantages offered in treatment by virtual and augmented reality on certain cognitive processes (Kang et al., 2021). Indeed, there are some high-quality studies which verify the clinical effectiveness of these techniques as non-pharmacological treatment (Díaz-Pérez & Flórez-Lozano, 2018; Optale, Urgesi, Busato, Marin, Priftis et al., 2010; Man, Chung, Lee, 2011). However, the difference in approaches and the evaluation tools employed, among other aspects, may explain the differences found among the studies (Liao, Chen, Lin, Chen, Hsu, 2019; Hwang, Choi, Choi, Park, Hong, Park, Yoon, 2021).

Beyond this, it has been considered essential to incorporate certain aspects of an interactive nature to enable people to work on and recover basic everyday skills, mainly in the area of cognitive intervention, although the development of activities which complement the work on cognitive and physical functions is also seen as essential.

The main contribution of this study is that it shows that, at present, although no statistically significant data have been found, it is possible to appreciate slight improvements which suggest that virtual and augmented reality are complementary tools. These techniques have extremely useful interactive features for exercising and recovering basic skills for everyday life, particularly in the cognitive field. This can, without doubt, contribute to research on programmes based on physical and cognitive stimulation in older adults and to evaluate their effects after their application.

The development of a methodology for working in virtual environments may make it possible to develop techniques for cognitive evaluation, strategies for cognitive rehabilitation and therapeutic activities can which contribute towards improving the quality of life of older adults who make use of social resources of an institutional nature and in their home environments. It is, therefore, essential to personalise the processes of care and integral attention in a working model based on the guarantee of participation and social and cultural inclusion of older adults and, in such a way, to prevent social isolation and other negative factors deriving from age.

Note.

The researchers are grateful for the support of the Mimo day centre (Murcia, Spain).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arévalo-Rodríguez, I., Smailagic, N., Roqué i Figuls, M., Ciapponi, A., Sánchez-Pérez, E., Giannakou, A., et al. (2015). Mini-Mental State examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer´s disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database system revisión,3.

- Botella C, Fernández-Álvarez J, Guillén V, García-Palacios A, Baños R. (2017) Recent Progress in Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Phobias: A Systematic Review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. Jul;19(7):42. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0788-4. PMID: 28540594.

- Díaz-Pérez, E., Flórez-Lozano, J.A. (2018). Realidad Virtual y demencia. Revista de Neurología, 66, 344-352.

- Hwang, N., Choi, J., Choi, D., Park, J., Hong, C., Park, J., Yoon, T. (2021). Effects of semi-immersive virtual reality-based cognitive training combined with locomotor activity on cognitive function and gait ability in community-dwelling older adults. Healthcare, 9, 814.

- Kang, J. M., Kim, N., Lee, S. Y., Woo, S. K., Park, G., Yeon, B. K. & Cho, S. J. (2021). Effect of cognitive training in fully immersive virtual reality on visuospatial function and frontal-occipital functional connectivity in predementia: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research,23(5).

- Liao, Y., Chen, I., Lin, Y., Chen, Y., Hsu, W. (2019) Effects of virtual reality-based physical and cognitive training on executive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized control trial. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 1

- McEwen D, Taillon-Hobson A, Bilodeau M, Sveistrup H, Finestone H. (2014). Virtual reality exercise improves mobility after stroke: an inpatient randomized controlled trial. Stroke. Jun;45(6):1853-5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005362. Epub 2014 Apr 24. PMID: 24763929.

- Maples-Keller, JL, Yasinski, C, Manjin, N, Rothbaum, BO. (2017). Virtual Reality-Enhanced Extinction of Phobias and Post-Traumatic Stress. Neurotherapeutics Jul;14(3):554-563. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0534-y. PMID: 28512692; PMCID: PMC5509629.

- Man, D.W., Chung, J.C., Lee, G.Y. (2011). Evaluation of a virtual reality-based memory training programme for Hong Kong Chinese older adults with questionable dementia: a pilot study International Journal of Geriatric_ Psychiatry, 27, 513-520.

- Myeong, J., Kim, N., Young, S., Kyun, S., Park, G., Kil, B., Woon, J., Youn, J., Ryu, S., Lee, J., Cho, S. (2021). Effect of cognitive training in fully immersive virtual reality on visuospatial function and frontal-occipital functional connectivity in predementia: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical internet research, 23(5).

- North, M. M., North, S. M., & Coble, J. R. (2015). Virtual reality therapy: An effective treatment for the fear of public speaking. International Journal of Virtual Reality, 3(3), 1–6. doi:10.20870/IJVR.1998.3.3.2625

- ONU (2020). Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 14 December, United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021-2030). A/RES/75/131, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3895802?ln=es

- Optale, G., Urgesi, C., Busato, V., Marin, S., Piron, L., Priftis, K., et al. (2010). Controlling memory impairment in eldery adults using virtual reality memory training: a randomized controlled pilot study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 24, 379-390.

- Roth, M., Huppert, F., Mountjoy, C.Q., Tym, E. (1998). CAMDEX-R. The Cambridge examination for mental disorders of the eldery – revised. Cambridge University Press

- Sangari M, Dehkordi PS, Shams A. (2022). Age and attentional focus instructions effects on postural and supra-postural tasks among older adults with mild cognitive impairments. Neurol Sci., 43(12):6795-680 doi: 10.1007/s10072-022-06355-7.

- Vega J, García P, Camacho Lazarraga, Caraballo Vidal I. (2018). La realidad virtual como herramienta en el uso de tratamientos mentales y físicos. Avances de investigación en salud:volumen IV/coord. por Mª C. Pérez Fuentes, J. J. Gázquez Linares, Mª M Molero Jurado, Á. Martos Martínez, A. B. Barragán Martín, Mª M Simón Márquez, págs. 65-69.