Archive : Article / Volume 1, Issue 2

- Research Article | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-2179/006

Modelling attitude towards HIV / AIDS in literature from 2019 to 2021

Departent Psychology, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, San Juan del.

Sonia Sujell Velez-Baez

Sonia Sujell Velez-Baez, Sofia López de Nava-TapÃa, Cruz GarcÃa-Lirios, (2022). Modelling attitude towards HIV / AIDS in literature from 2019 to 2021, Journal of Microbes and Research. 1(3). DOI: 10.58489/2836-2179/006

© 2022 Sonia Sujell Velez-Baez, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 22-10-2022

- Accepted Date: 14-11-2022

- Published Date: 26-12-2022

Identity; stigma; attitude; reliability; validity

Abstract

In the framework of health policies, the psychological processes of dentistry and stigma are a binomial that tries to explain lifestyle assessment processes related to vulnerable groups. Precisely, the objective of the present work is to establish the validity and reliability of an instrument that measured both dimensions on an attitude scale. A cross-sectional and correlational study was carried out in order to establish the psychometric properties of the instrument with a non-probabilistic and intentional sample of 100 students from a public university. Results showed that both dimensions as preponderant factors attitude, but its inclusion in the construct was assumed as part of a spontaneous activation process; actions and risks that only a group or close to carriers of HIV / AIDS can take.

Introduction

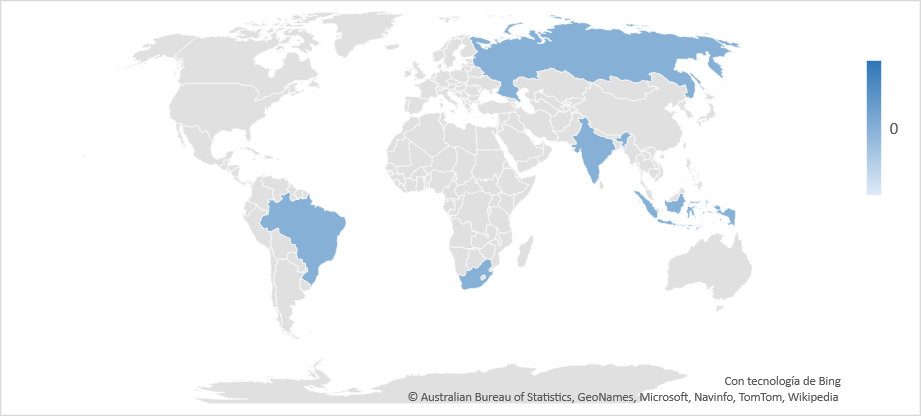

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a public health problem due to the incubation and development process [1]. HIV cycle comprises a standard period of 10 years in which those infected are still risky lifestyles because they do not change their behavior that requires them to self-care [2]. The process of infection and reinfection is more likely, because since the pl membrane to SMICA and CD4 receptor are infected until processed viral RNA and new version is reconstructed, diagnoses are inconclusive and proliferates the spread of the virus in people with risky behaviors [3]. Because of the way of getting the disease, lifestyles of risk that can be observed anywhere in the world and could be associated with beliefs and attitudes toward carriers, as well as groups to which they belong (see Figure 1).

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a public health problem due to the incubation and development process [1]. HIV cycle comprises a standard period of 10 years in which those infected are still risky lifestyles because they do not change their behavior that requires them to self-care [2]. The process of infection and reinfection is more likely, because since the pl membrane to SMICA and CD4 receptor are infected until processed viral RNA and new version is reconstructed, diagnoses are inconclusive and proliferates the spread of the virus in people with risky behaviors [3]. Because of the way of getting the disease, lifestyles of risk that can be observed anywhere in the world and could be associated with beliefs and attitudes toward carriers, as well as groups to which they belong (see Figure 1).

Note: Elaborated with data OECD (2021)

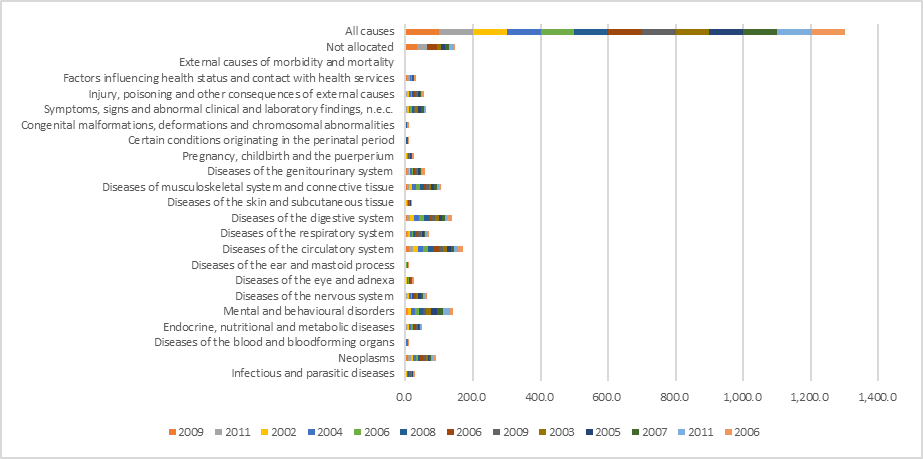

Thus, 30.1 million of HIV cases are adults, 16.8 million women and 1.5 million children [4]. Sub - Saharan Africa has the largest number of carriers with 22,900,000 while the North d?? and Africa recorded 470 thousand cases, in some cases used as a point and another to separate units [5]. In Latin America there are 1,500,000 carriers and in Mexico only 200,000 cases [6]. Both aspects, the process of infection transmission and the disproportionate increase in the regions seem to indicate that the problem has its origin in the risk behaviors themselves that, being influenced by the identity of carrier and non-carrier groups, make HIV a problem of public health related to stigma (see Figure 2).

Note: Elaborated with data OECD (2021)

In health sciences, groups close to patients are known as social support and are a predominant factor in adherence to treatment, the main determining variable of hospital health. In the case of groups close to HIV / AIDS carriers, they are not only associated with risk styles, but risk identities are attributed to them [7]. In the virtual classroom, adherence to treatment would be a central axis in the health training agenda and the promotion of healthy lifestyles such as self-control; self-care and self-efficacy [8]. This is the case of the rehabilitation of athletes who assume adherence to treatment as an extension of their lifestyle focused on achieving objectives, tasks and goals.

Identity and stigma are two psychosocial processes that for the purposes of this work should be understood as attributions and biased choices in favor of a group of belonging with respect to another reference group [9]. On the electronic whiteboard, the diffusion of a self-centered identity involves the significant learning of treatment adherence strategies such as medication follow-up or monitoring of vital signs [10]. In contrast, the stigma would be linked to legitimate risk behaviors from the exclusion of people other than the individual and the group to which he belongs or wishes to belong. In this way, attitudes towards HIV / AIDS are a reflection of self-control, self-care and self-efficacy, either against or in favor of preventive or risky lifestyles [11]. Both processes, they underlie when considering HIV / AIDS as a public health problem, which makes sense in an economic, political, social, healthcare, symbolic, institutional, organizational, professional context (Table 1).

Table 1. Social context of public health.

Context | Dimensions | Factors | Interventions | Indicators |

Politician | Commitment | Construction of agenda | Establishment of agreements | Percentages of agreements established according to social and local conditions |

Symbolic | Norms, meanings, ideologies, visions | Power, stigma, discrimination, influence | Mediation, framing, awareness, advocacy, transformation | Percentages around beliefs related to the action of the closest other |

Material | Economy, praxis | Poverty, capacities, criminalization | Production, redistribution, capacity, | Percentages of exclusion and marginality of care |

Relational | Intra and inter communities, entities, instances | Capitals, participation | education, initiatives, mobilization | Organizational and advisory, deliberative or consensual participation percentages |

Institutional | Structure, incidence, prevalence | Vulnerability, marginality, exclusion | Specializedcare, focusedtreatment | Establishment of costs and financing, hospital structure and modern facilities, mortality, orphanhood and risks; percentage of cases in specific sectors diagnosed with standardized procedures |

Organizational | Performance, capacity, quality | Relationship and taskclimate | Reengineering, synergy | Strategic alliances in terms of volunteer training, management and promotion processes, Percentage of applicants for diagnosis and case monitoring, risk communication and health promotion |

Assistance | Knowledge, behavior, adherence, representation, happiness, influence | Promotion, management, quality of life and subjective well-being | Channeling, monitoring, mediation, promotion, management | Percentage of self-care and coping around the problem, formation of positive attitudes |

Source: Mannellet al, (2014)

Attitudes, identity is a result of a deliberate, planned and systematic election. In this sense, there are three attitudinal theoretical frameworks that would explain the favoritism of the endogroup to the detriment of the outgroup known as ethnocentrism, although a conflict within the group of belonging would generate an alter centrism [12]. It is known that the identity or choice of a risky or healthy life depending on the group of preference or belonging, influences preventive or risky behaviors [13]. In the virtual classroom, the teaching of both dimensions can be carried out based on group dynamics in which the participants select the resources and capacities to face a life with HIV / AIDS.

The theory of reasoned action (TAR) argue that identity and stigma are products of processing general information about a group belonging to the powers in contrast to a control group [14]. In this conceptual model, beliefs process the surrounding information, but it is attitudes that will determine the biased choice of a group [15]. These are categories in which the information is concentrated to carry out a specific action that exalts the in-group and sidesteps the out-group [16]. Theories of rational choice; reasoned action and planned behavior are distinguished by generating an ideal behavior scenario for the promotion of health and the prevention of diseases such as accidents [17]. On the electronic board, this paradigm is used to establish groups and compare their responses to an uncertain situation such as HIV / AIDS.

However, the resulting deliberate action, categorized from general information, did not always anticipate specific behaviors and would rather require perceptions of control or perceived behavioral controls [18]. This is how the Theory of Planned Behavior (TCP) assumes that only the delimited information and its processing, both of beliefs and perceptions, will specify the information in a way that would anticipate specific behaviors [19]. By virtue of its specificity in the prediction of a behavior, the planned behavior suggests an internal discussion scenario in which the individual represents himself as a risk or prevention factor in a dynamics of variables that determine contagion, or the adherence to treatment once this infection has occurred.

Thus, from the perspective of the TAR and the TCP, the identity and the stigma are consequences of having deliberately processed, planned and systematic information concerning a group close to an individual after being contrasted with information on other groups distant that same individual [20]. Both theories suggested that health education and promotion are the result of dialogue, consensus and responsibility among stakeholders, assuming that they have the necessary information to make decisions inherent in situations and forecasts of fatalistic, realistic and pessimistic scenarios.

Although attitudes have been considered as associations between evaluations made from group categories, the Theory of Spontaneous Processing (TPE) maintains that attitudes are rather arbitrary, spontaneous or semi-automatic processes [21]. The spontaneous activation proposal suggests that in a limit situation, those who are carriers of HIV / AIDS will have to assume the consequences of their actions in an unprecedented way, whenever they discard the possibility of managing risks [22]. In the virtual classroom, this automatic process is generated at a time when technology is not enough to discuss the implications of a drug or treatment on the health of patients.

The TPE, unlike the TAR and the TCP that propose a deliberate, planned and systematic process, considers that this information is protected in the long and short-term memory, as well as in its procedural phase. In this way, the information is stored and is in a state of latency that will be activated when some stimulus retrieves it and associates it with improvised behavior [23]. Identity and stigma, from the perspective of TPE, are part of the arbitrary, spontaneous or semi-automatic process that characterizes attitudes [24]. In this sense, it is noted that identity is a negative or positive attitude, for or against a group and stigma is a biased evaluation of said attitudinal and identity process, but that for some reason it is latent and does not materialize as a behavior until a stimulus reactivates the discretion of the individual by categorizing groups related to carriers of a disease such as HIV/AIDS.

From TAR, TCP and TPE it is possible to build a theoretical framework in which both deliberate and spontaneous processes, planned with discretionary, systematic with semi-automatic coexist [25]. In this model, the information did not flow from one side to the other or is interconnected from one extreme to the other, but is in the entire cognitive structure of the individual, evidencing the formation of a network.

The Attitudinal Network Theory (TRA) maintains that both identity and stigma are not only correlated with attitudes, but they are also structural nodes from which information is resignified to form new nodes; associations between categories and evaluations around information concerning the in-group and out-group [26]. Psychological studies of attitudes, identity and stigma pose a cognitive network to explain the relationships between groups and carriers of HIV / AIDS.

The cognitive network is a process of social responsibility in which the carriers not only demonstrate self-care, but also disseminate their experiences in order to prevent re-infections or contagions that lead to a health problem public [27]. The expressiveness of the disease a network structure associated with social responsibility and solidarity with carriers in the terminal phase [28]. A network of symbols determining the recruitment of victims of sexual exploitation that developed undervaluation, risk and recidivism behaviors. Among the risky sexual behaviors is coitus interruptus to a network of beliefs about invulnerability of young people with respect to the spread of HIV or the non- development of AIDS. In this sense, warned that when couples establish a communication network, their decisions are made by consensus, but when only one-way communication is established, men delegate responsibility for contraception to women [29]. For his part, when a group is exploited by pimps, the latter establish discourses that legitimize the superiority of residents or natives with respect to migrants [30]. In this same sense, inventory of sexual assault experiences established a link with current sexual experiences, victims are not always considered exploited and rather are their religious beliefs about the Sin those that affect their sexual behaviors.

The objective of the present work is to establish the dimensions of the attitudes towards carriers of HIV / AIDS, considering a scenario of social health services. In this sense, the contribution of the work to the health sciences and the state of the question lies in: 1) systematic review of contextual, theoretical, conceptual and empirical frameworks, 2) methodological approach to the phenomenon; 3) diagnosis of the attitudinal factors that determine risk or prevention behaviors, 4) discussion of the advances and setbacks in the matter; 5) applicability of the results in the virtual classroom.

What are the psychosocial dimensions of groups close to carriers of HIV/AIDS: in a public health context, around which information is generated regarding lifestyles, risk behaviors, violence and sexual exploitation?

The identity and stigma reported in the state of knowledge regarding groups close to carriers of VIH/AIDS: they would not only be preponderant factors in their study, but they would also be psychosocial effects of the information related to lifestyles and behaviors of risk, violence and sexual exploitation scattered in the perceptions, beliefs, attitudes and discourses of groups with which family and friends of people living with HIV / AIDS interact [31]. In this sense, both identity and stigma are two representative and discursive nodes from which information concerning public health risks is processed [32]. In other words, the information attributed to groups vulnerable to HIV / AIDS justifies and legitimizes the sexual division between those groups that deliberate, plan and systematize their intercourse before the groups that arbitrarily and improvise have sexual encounters.

Method

It is out exploratory traverse correlation study. A non-probability selection was made of 100 students from a public university in the State of Mexico.

Sex. 49% of the respondents were women (M±SD = 339.45±21.37 $ of monthly income), 48% were men (M±SD = 384.58±19.36$) and 3 % did not answer how relevant is reporting income? How does it help in research?

Age. 51% were between 22 and 29 years old (M±SD = 326.38±21.25 $ monthly income), 37% were between 18 and 22 years old (M±SD = 273.29±18.0$), 9% were under 18 years old (M±SD = 220.13 ±10.6 $), 3% did not answer the same way, what does knowing age help?

Group. 63% stated that they did not belong to any particular group (M = 257, $ 27 monthly income and SD = 19.08), (M = 345, 24 and SD = 17.20).

Preferences. 82% indicated that he is preferably heterosexual (M = $ 259.40 monthly income and SD = 37.29), 15

Results

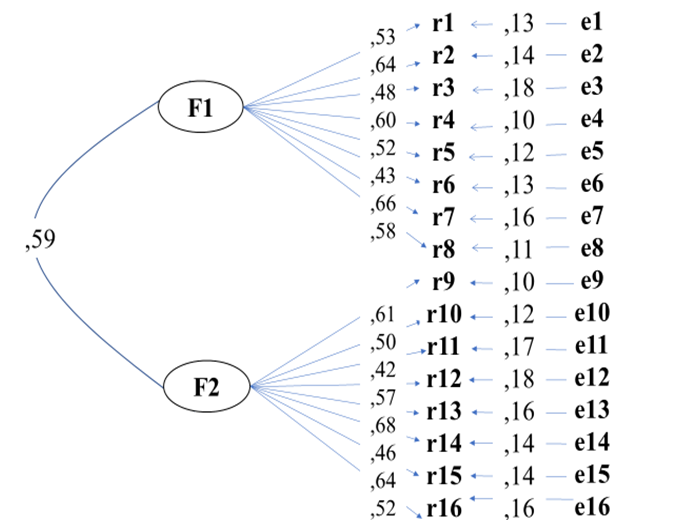

The Table 2 shows values above 0.70 for the items that were measured by two subscales concerning the identity and stigma as preponderant factors was the attitude towards HIV/AIDS: which was established over 0,300 factor weights therefore which explained 43% and 57% of the total variance.

Table 2. Psychometric properties of the instrument

R | M | SD | V | H | A | F1 | F2 |

r1 | 2.83 | 0.10 | 17.31 | 2.45 | 0.739 | 0.536 |

|

r2 | 2.49 | 0.13 | 15.46 | 2.57 | 0.725 | 0.406 |

|

r3 | 2.83 | 0.15 | 16.21 | 2.13 | 0.739 | 0.514 |

|

r4 | 2.96 | 0.94 | 11.43 | 2.08 | 0.748 | 0.578 |

|

r5 | 2.77 | 0.85 | 15.67 | 2.76 | 0.745 | 0.351 |

|

r6 | 2.49 | 0.71 | 10.21 | 2.43 | 0.741 | 0.362 |

|

r7 | 2.61 | 0.39 | 19.13 | 2.43 | 0,756 | 0.462 |

|

r8 | 2.84 | 0.31 | 17.54 | 2.89 | 0,772 | 0.468 |

|

r9 | 2.90 | 0.48 | 19.34 | 2.54 | 0.704 |

| 0.591 |

r10 | 1.04 | 0.57 | 18.56 | 2.43 | 0.714 |

| 0.493 |

r11 | 1.05 | 0.26 | 14.36 | 2.56 | 0.726 |

| 0.491 |

r12 | 1.92 | 0.83 | 13.21 | 2.13 | 0.701 |

| 0.384 |

r13 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 17.65 | 2.67 | 0.735 |

| 0.412 |

r14 | 1.07 | 0.99 | 14.32 | 2.43 | 0.794 |

| 0.485 |

r15 | 1.01 | 0.80 | 19.21 | 2.14 | 0.752 |

| 0.384 |

r16 | 1.82 | 0.74 | 12.14 | 2.09 | 0.734 |

| 0.461 |

Note: Elaborated with data study; R = Reactive, M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, V = Variabilidad estimada con Mardia, H = Homocedasticidad medida con Levene, Bootstrap = 0.000; Kurtosis = 1, 304; KMO = 0.7 21; Bartlett test [χ 2 = 18,33 (18 gl) p = 0.000], F1 = Attitude towards the identity of groups close to HIV/AIDS carriers (23 % of the total variance explained), F2 = Attitude towards the stigma of groups close to carriers of HIV/AIDS (17 % of the explained variance)

Internal consistency and the construct validity of the instrument signal can be replicated in other contexts with other samples, but last must be university students since the selection of the sample was not random. Once the validity of two explanatory factors of 40% of the total variance had been established, their relationship structure was estimated in order to investigate the influence of other factors not included in the model (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations and covariations

| M | SD | F1 | F2 | F1 | F2 |

F1 | 23,12 | 14,21 | 1,000 |

| 1,897 | ,652 |

F | 21,26 | 11,43 | ,450** | 1,000 |

| 1,976 |

Note: Elaborated with data study; R = Reactive, M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation; F1 = Identity, F2 = Stigma *p < ,01; **p < ,001; ***p < ,0001

The trajectories of relationships between the factors were estimated once their correlation and covariance were demonstrated, assuming high values for each indicator of each factor and low associations between the two (see Figure 1).

Note: Elaborated with data study; R = Reactive, e = Error of measurement of indicator

The adjustment and residual parameters ⌠χ2 = 12,34 (13df) p > ,05; CFI = ,990; NFI = ,995; GFI = ,997; RMSEA = ,007⌡suggest the non-rejection of the null hypothesis regarding the adjustment of the relationships between the factors established in the literature review with respect to the relationships observed in the present work. The non-significant differences observed among variables studied (the non-rejection of the null hypothesis) should be discussed biologically in details.

Discussion

The present study has established the validity and reliability of an instrument that measures the attitude towards identity and stigma of groups close to carriers of HIV / AIDS in a context in which the media, mainly television, was assumed to be the source Most informative information regarding lifestyles and risk behaviors, as well as vulnerability to sexual exploitation by those who interact with people living with HIV / AIDS. In the virtual classroom, the teaching of roles is essential for meaningful learning of topics. In the case of attitudes towards HIV / AIDS, identity and stigma play a fundamental role in establishing collaborative groups united by common resources.

Identity of gender to the time of sex between parents and children and concluded that not only the sexual subject was taboo, but was also guided by a vision of female gender more than a male gender identity.37 In this sense, the present study warned that gender identity would be linked to stigma, since they are two informative nodes that, although influenced by the media, guide the formation of attitudes towards the choice and reference of a heterosexual group with respect to a homosexual group.

Adolescences who start their sexual relations are more influenced by their peers than by their parents, teachers, social groups or digital networks. Identity seems to be a proc and so that not only explicit sexual preference, but also practice and the frequency thereof to improvise or when planning a sexual act. In the present study, it was only established that the respondents not only distinguish their group from belonging to the reference group in question (family and friends of HIV / AIDS), but also note an attribute trend that makes them evaluate these groups as different from associate them with lifestyles and risk behaviors typical of a sector vulnerable to sexual exploitation.

Finally, with respect to the study by García (2013) in which the group of health professionals stigmatized care for family members and carriers of HIV / AIDS as a vulnerable group that should be cared for differently than the other groups of relatives and patients, the present work considers that identity is not only evaluated by the respondents, but is also linked to associations that place vulnerable groups in risky practices and sexual exploitation.

However, this work does not explain how identity and stigma are nodes of attribution of information concerning lifestyles and risk behaviors in an environment of sexual exploitation, but it does show that both identity and stigma are components of a construct related to attitudes towards groups related to carriers of HIV / AIDS. In other words, the study may or may not verify that identity and stigma are nodes where information is concentrated or generated, but it opens the discussion about the importance of observing the relationship between vulnerable, marginalized or excluded groups around carriers of HIV/AIDS are part of a social support largely determines adherence to treatment.

Conclusion

The contribution of the present work to the state of knowledge is to have established the validity and reliability of an instrument that measures two preponderant psychosocial factors in the formation of attitudes towards groups close to carriers of HIV/AIDS. According to the Theory of Processing is spontaneous, memory not only safeguards information regarding HIV/AIDS, risk styles and behaviors of vulnerable groups, but also such information is spontaneously or arbitrarily activated to carry out improvised behaviors that would explain self - care. The yellow is not a conclusion of this work, but the perspective supported by the TPE theory, which on the other hand was not verified with what was reported. In this sense, identity and stigma would be the result of the information disseminated in the media but would indicate the emergence of a psychosocial process regarding power or social influence around sexuality.

References

- Organization for Economic and Cooperative Development. Statistical for HIV / AIDS in countries. OECD 2021 https://data.oecd.org/searchresults/?q=hiv

- World Health Organization. Statistical for HIV / AIDS disease in the world. WHO 2021 https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-05-2021-update-from-the-seventy-fourth-world-health-assembly-27-may-2021

- Panamerican Health Organization. Statistical for HIV / AIDS in the Americas. PAHO 2021 https://www.paho.org/en/topics/hivaids

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informativa. Statistical for HIV / AIDS in Mexico. INEGI 2021 https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/denue/Default.aspx?idee=190315

- Secretaria de Salud Publica. Statistical for HIV / AIDS in CDMX. SSA 2021 https://www.gob.mx/censida

- Abbasi A, Rafique M, Aziz W, Hussai W. (2013), Human immunodeficiency virus / acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV / AIDS): Knowledge, attitudes of university students of the state of Azad Kashmir (Pakistan). J AIDS & HIV Res; 5, 157-162

- Afanador A. (2014), Particularities regarding the formation of sexuality in adolescents. His Ame Psy Not; 13 (2), 91-104

- Albacerrin D, Wyer R. (2011), Elaborative and non-elaborative process a behavior related communication. Per Soc Psy Bul; 27, 691-705

- Aramayo S. (2011), Therapy focused on solutions applied to sexual assault. Case study. Ajayu; 9, 132-168

- Becerra V, Chunga N, Palomino C, Arévalo T, Nivin J, Portocarrero L, Carbajal P, Tomás B, Caro M, Astocaza L, Torres L, Carbajal E, Pinto A, Moras M, Munayco M, Gutiérrez C. (2012), Association between knowledge of Peruvian women towards HIV and their attitudes towards infected people. Per J Epi; 16, 1-8

- Cañizo E, Salinas F. (2010), Alternate sexual behaviors and permissiveness in university students. Tea Res Psy; 15, 285-309

- Castillo A, Chinchilla Y. (2011), The experience of the psychology school of the University of Costa Rica in dealing with commercial sexual exploitation. Lat Ame J Hum Rig; 22, 121-151

- Chacón M, Barrantes K, Comerfold M, McCoy C. (2014), Practices sexual and knowledge about HIV / AIDS among drug users in a low - income community in Costa Rica. Hea Drugs; 14 (1), 27-36

- Davis M, Shell A, King S. (2012), Assessing pharmacist 'perspectives of HIV and the care of HIV-infected patients in Alabama. Pha Pra; 10, 188-193

- Ferragut M. Ortiz M. (2013), Psychological values as protective factors against sexist attitudes in preadolescents. Psicothema; 25, 38-52

- García C. (2013), Attitude of social workers towards carriers of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus in community health centers. Hea Soc; 4 (1), 60-68

- García I. Rodríguez M. (2014), Situation in which they live and adherence to treatment in women and youth of San Luis Potosí with HIV / AIDS. Uni Act; 24 (4), 3-14

- Giraldo I. (2013), Cyberbodies: youth and sexuality in postmodernity. Res New Edu; 13, 1-22

- Hernández I. (2013), Making way while walking: Migration, feminization and human trafficking in irregular migration flows on the southern border of Mexico. Uni Dig Mag; 14, 1-15

- Hughes S. Barnes D. (2011), The dominance of associative theorizing in implicit attitude research: propositional and behavioral alternatives. Psy Res; 6, 465-498

- Hurtado N, Avandaño M, Moreno F. (2013), Pregnancy in adolescence: between informational failure and psychic achievement. Psy Mag Uni Ant; 5 (1), 93-102

- Jouen F, Zielinski S. (2013), Commercial sexual exploitation of minors in tourist destinations. Knowledge, attitudes and prevention of tourism service providers in Tananga, Colombia. Mag Tou Cul Her; 11, 121-134

- Klaus A, Piñeres J, Hincapie A. (2010), Subjectives language and parody: reflections around expert discourses on the commercial sexual exploitation of adolescent boys and girls. Lat Ame Jou Soc Sci, Chi You; 8, 269-291

- Mannell J, Cornish F, Russell J. (2014), Evaluating social outcomes of HIV / AIDS interventions: a critical assessment of contemporary indicators frameworks. J Int AIDS Soc; 17 (1), 1-11 https://dx.doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.19073

- Mardones R, Guzmán M. (2011), Towards a comprehensive treatment from the psychosocial model in sexually exploited children and adolescents. Sci J Psy; 2, 27-47

- Méndez M. (2013), It deals: invisible slavery in Costa Rica. Study of five cases. Cos Ric J Psy; 32, 109-135

- Méndez R, Rojas M, Moreno D. (2012), Commercial sexual exploitation of children: the life routes of abuse. Res Dev; 20, 450-47

- Petro B. (2013), Attitudes and views of teachers towards student sexual relationships in secondary school in Tanzania. Aca Res Int; 4, 232-241

- Rivers M. (2011), The uses of trafficking in Central America: migration, gender and sexuality. Cen Ame Stu Yea; 37, 87-103

- Rodríguez D. (2013), Advanced chronic disease, mental illness and the general system of social security in health. Psy Mag Uni Ant; 5 (1), 75-92

- Selesho J, Modise A. (2012), Strategy (ies) in daling with HIV / AIDS in our schools: changing the lenses. J Hum Eco; 38, 181-189

- Solat S, Velhal G, Mahajan H, Rao A, Sharma B. (2012), Assessment of knowledge and attitude of rural population about HIV / AIDS in Raigad Distrit, India. J Den Med Sci; 1, 31-45

- Summer L. (2011), The theory of planned behavior and the impact of the past behavior. Int Bus Eco Res J; 10, 91-110

- Uribe A. Orcasita L. (2011), Assessment of knowledge, skills, susceptibility and self-efficacy against HIV / AIDS in health professionals. Nur Adv; 29, 271-284

- Villa E. (2010), Anthropological study around prostitution. Cuicuilco; 17, 157-179

- Garcia C, Quintero M, Molina M. (2021), Modelling reproductive choice in the Covid-19 era. Env Res Pub Hea; 18 (1), 1-5

- Lopez S. Morales M, Garcia C. (2021), Specification of a model based on publishing findings from 1961 to 2020 for the study of reproductive choice. J Obs Gin Rep Sci; 5 (3), 1-4