Archive : Article / Volume 2, Issue 1

- Research Article | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-2179/011

Ecocity in the COVID-19 era

Department Psychology, Mexico University.

José Marcos Bustos Aguayo

J.M. Bustos Aguayo, C.G. Lirios, V.H. Meriño Cordoba, C.Y. Martinez de Meriño, (2022). Ecocity in the COVID-19 era, Journal of Emergency and Nursing Management. 1(3). DOI:10.58489/2836-2179/011

© 2022 José Marcos Bustos Aguayo, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 25-10-2022

- Accepted Date: 16-11-2022

- Published Date: 30-01-2023

Governance, ecocity, model, complexity, agenda

Abstract

The system of co-management and co-administration of public services known as governance has been extensively addressed in terms of its dimensions, but an analysis of the process has not been established so far. The objective of this work has been to confirm the factorial structure reported in the literature. Two studies were carried out, one exploratory and the other confirmatory to the factorial structure of the Expected Governance Scale of Carreón (2021), establishing three factors: expected resolution, perceptions of agreements and expectations of responsibilities, although the research design limited the findings to the sample of analysis, suggesting the extension of the model to other moderating factors such as leadership.

Introduction

Until February 2022, the pandemic has killed seven million, although another 13 million deaths are estimated due to indirect causes of COVID-19. Socially responsible cities undertook sustainability projects to increase their corporate image in the face of tourist and investor flows. Once the population has been immunized, the eco-city would immediately reactivate the local economy and contribute to the public treasury.

Broadly speaking, the governance of the eco-city refers to the establishment of indicators for local sustainability in which a cognition system is established, focused on co-responsibility. The concept of governance, for the purposes of this study, refers to a system of co-government of natural resources and. therefore, co-management and co-administration of municipal services, the main feature being co-participation and co-responsibility among political and social actors (Brites, 2012).

In the case of ecocity understood s as indicators of self - government, self - management, self - administration and self -responsibility, is a stage and an exclusive civil organization, the State and any other political system of government (Carreon, Hernández & García, 2014).

Well, the governance concept of the eco-city means:

1) an exacerbation of environmental problems, climatic disasters, natural catastrophes, atmospheric contingencies and ecological crises;

2) propaganda of the rectory of the State as the only alternative management and administration before the effects of climate change on environmental public health;

3) self-government, self-management and self-administration of the local heritage of communities and neighborhoods surrounding the cities;

4) establishment of a common agenda on policies, programs and co-government strategies, co-management and co-management of natural resources and public services (García, 2013).

Before the increase of the effects of the climatic change on the public health, it is necessary an unprecedented system of government in which governors and governed are circumscribed to an agenda, themes, discussions, consensus and co-responsibilities that overcome their differences and resolve conflicts that impede sustainable local development. In such a process, negotiation, mediation, conciliation, arbitration and prosecution of responsibilities are necessary (García et al., 2016).

Therefore, the objective of this paper is to make a model for the study of the governance of the ecocity more complex. A documentary, cross-sectional and exploratory research was carried out with a selection of information sources indexed to national repositories such as Latindex and Redalyc, considering the period of publication from 2019 to 2022, the inclusion of the keywords: "Climate change", "governance", "Ecocity". The information was processed from the Delphi technique in order to establish the model.

Theory of ecocity

The theoretical frameworks that explain the governance of the ecocity are: 1) The Theory of Capabilities, 2) The Theory of Habitus and 3) The Theory of Spatiality.

The city as a scenario of symbols, meanings and meanings around which the asymmetries between public policies and urban lifestyles are represented. The city is a scenario of resources that increase capacities, but also increase responsibilities (Bourdieu, 2002).

Studies related to real estate services; spatial and technological indicate that the size of the houses and the technology of their facilities, to be increasingly reduced the first and more automated the second, facilitate fluvial catchment and recycling, but inhibit the storage and reuse of water. Provision capacity seems to encourage the irresponsibility of waste of water (García, Carreón & Quintero, 2016).

The Theory of Capacities implies an interrelation between resources, services, scenarios, skills, knowledge and responsibilities that would make necessary a governance system from which the balance between the mentioned factors is regulated by the State, supervised by the citizenship and financed by the market (Gissi & Soto, 2010).

However, from a developmental policy framework in which freedoms will give way to capabilities and responsibilities. This process seems to be inhibited given the scarcity of natural resources in cities. That is, the availability of resources, being an objective fact rather than a subjective one, influences the lifestyles of the users who inhabit the cities (Guillén, 2010).

Such scarcity phenomenon activates public policies that seek to supply resources to one social sector to the detriment of another. In response to the exclusion or marginalization of public services, the segregated population constructs habitus intuito, adopts lifestyles from which they will confront symbolically and actively with the authorities. Protests, closures, rallies, demonstrations, marches, physical or verbal confrontations are the result of scarcity of resources, public policies and lifestyles or habitus of citizenship (Lefébvre, 1974).

Studies on life-styles in cities in terms of shortage, saving and water reuse show that availability of less than 50 liters per person per day increases austerity, but increases confrontations with local authorities; kidnappings of pipes, closures of avenues, boycotts to networks and clandestine takes. Citizens segregated from water spaces and public services, develop skills and strategies to demonstrate the situation in which they find themselves, express their outrage and appropriate spaces (Malmod, 2011).

In the framework of water conflicts between authorities and users, the Theory of Habitus states that citizens' lifestyles in a situation of scarcity are a consequence of public policies. The city is a field of interrelation between capitals and socially constituted habits. In this way, economic and political capitals are confronted with natural and citizen capitals. That is, the market and the State require aquifers that supply the industry and private services as publics of the city, but the availability of water, through the recharge of aquifers, is increasingly lower than international standards or registries. national historical. Such a scenario explains the emergence of habitus or lifestyles in vulnerable, marginalized or excluded sectors (Iglesias, 2010).

However, the Theory of Habitus maintains that lifestyles are conjunctural, emergent and inherent to a group or social agent. In other words, in a situation of scarcity and shortage, austerity underlies and similarly disappears in a situation of water sustainability in which the recharge of aquifers would guarantee the human and local development of the demarcations of a city. Such an approach is insufficient if it is necessary to understand the historical process that led cities to concentrate resources, services, lifestyles and capacities (Loyola & Rivas, 2010).

The Theory of Spatiality’s understands the city as a symbolic scenario in which the relations of production materialize. The city concentrated asymmetric economic relations between the classes that own the means of production and the labor force. In this sense, the city is a scenario of industrial production rather than services since the asymmetric relations between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat prevail over other asymmetric relations. The consciousness of space is no longer necessary to appropriate the factory, but the city that houses it. The right to the city would be the extension of the right to a symmetrical production relationship (Sen, 2011).

If the labor force only appropriates the means of production, the spaces would be only an accessory to the class struggle rather than a constitutive element of the differences between these classes (Santamaría,2012).

The Theory of Capacities explains the redistribution of resources and their impact on human, local and sustainable development. The differences between individuals (sex, age, skills, education, locality) determine the freedoms that individuals need to develop sustainably. In this sense, capacities are knowledge and experiences derived from the interrelation between individual characteristics, resources and spaces. As resources are scarce, capacities are decimated, and spaces are scenarios of conflicts as the state limits freedoms to ensure a proportional distribution of resources. In the case of water, the capacities play a fundamental role since the daily use of water implies the development of lifestyles or habitus that can help to counteract the situation of scarcity and shortage (Molini and Salgado, 2010).

The Theory of Habitus explains that the discrepancies between local water supply policies and self-management actions, closure of floods, network intervention, sequestration of pipes and boycotts to the system are the result of transformations of resources and spaces to the that a sector of the citizenry does not have access. If capacities and habitus are indicators of the conflicts between citizens' expectations and public decisions, then reappropriation of spaces for debate on the right to the city, its resources and water supply systems as well as water distribution is fundamental. (Vieira, 2012).

The Theory of Spatiality's introduced the category of power to explain the differences between the relations of symbolic and material production. The City stands as a symbol of power that homogenizes the relations of production because the material conditions for the same are already pre-established spatially. That is to say, spatial relations are relations of power, but not communicative or discursive relations, but material, although their fetishization makes them appear as tangible objects, but only at a discursive level, such relationships could be transmuted (Pallares, 2012).

The fetishism of space as a commodity undermines the principle according to which the material conditions of existence determine the ideological superstructure. This is so since the exaltation of objects is inherent in the value of their use. The space, real or symbolic, would have a value of use, but not of change, although the interesting thing about its fetishization is that it indicates the degree of alignment to capitalist production relations over any other type of relations in which spaces were not they are transformed into merchandise (Verissimo, 2012).

In a certain way, the capacities and the habitus would be precedents to the alignment and would be indicated by their degree of fetishistic representation of space. If capacities and habitus are skills circumscribed to resources and spaces, then the alignment would be the result of the scarcity of resources and the asymmetric distribution of resources. The scarcity of fetishized water in short supply would mean the emergence of saving skills or dosage habitus, but such a process would inhibit the representation of conflict and social change. that is, scarcity, shortage, confrontation or boycott indicate a pseudo-conflict as it is resolved by supplying pipes, the distribution of jugs, the regular provision of water or the granting of vouchers for the purchase of water. The contradictions between public policies and lifestyles, derived from the demand of the pharmaceutical, soft drink or beer market, are reduced to distribution relationships rather than production or space allocation (Brites, 2012).

The fetishization of space prevents observing the differences between social relations and their stratifications based on mechanisms of spatial and economic segregation. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the Theory of Spatiality's as a socio-historical complement to the categories of habitus and capabilities which are a-historical considering them emerging or underlying the absence of freedoms or the generation of abstract conflicts between the structure (public policies) and agency (Urquieta & Campillo, 2012).

The Theory of Capacities, the Theory of Habitus and the Theory of Spatiality's allow us to approximate the systems of governance of natural resources, mainly water resources, to the lifestyles of the users in reference to the public policies of water supply and irregular supply. In this regard, the reconceptualization of local governance systems will allow greater equity between the sectors through a normative legal framework of the right to the city in general, natural resources and public services at the local level and the comfort of water in the particular (Paniagua, 2012).

However, the urgency of a fairer political system around the citizenship of the cities, ecocity projects are multidimensional and, in this diversity, lies its complexity.

Ecocity studies

The conceptual frameworks that explain the governance of eco-science are: a) freedom, b) fields, c) capacities, d) capitals and e) responsibility (see Table 1).

Table 1. Ecocity studies

Year | Author | Find |

1980 | Berk et al., | They carried out a study in which they demonstrated a direct, positive and significant relationship between water supply reduction programs and residence savings as the strategy intensified in urban areas. |

1987 | Corral et al., | They found, in an exploratory study of frequencies of domestic water use, around the use of the shower, the main activity of domestic water consumption. In contrast, the use of the refrigerant was the domestic device with less frequency of use in both samples of the study. |

1992 | Corral and Obregón | They carried out a systematic review of the variables included in the models of pro-environmental behavior. They proposed factors, situations, pro-environmental competences, styles and ecological reasons as the determinants of Pro-environmental behavior. |

2000 | Corraliza and Martín | with a sample of 420 residents in Madrid Spain, they showed that attitudes determine (R 2 = .09; p <.01) the behavioral factor of waste. |

2001 | Corral | with a sample of 280 inhabitants of Ciudad Obregón Sonora, it showed that the observed water savings are indirectly determined by the water shortage (R 2 = .30) and by the reasons for saving water (R 2 = .22). |

2001 | Corral, Frías and González | They demonstrated through a factorial model ⌠X 2 = 26, 25gl; p = .36; NNFI = .95, CFI = .96; RMSEA = .02 ⌡ the direct, positive and significant effect between antisocial behavior on water waste (β = .35). |

2002 | Bustos et al., | With a sample of 202 inhabitants of Nezahualcóyotl and Chimalhuacán in the State of Mexico and the Federal District, it showed that the reasons predict personal hygiene (R 2 = .16). |

2002 | Corral | Established by means of a structural model ⌠X 2 = 43; 34 gl; p = .47; NFI = .95; NNFI = 1; CFI = 1 ⌡ that watering plants, washing dishes and brushing teeth are indicators (R 1 = .53, R 2 = .76 and R 3 = .75 respectively) of the skills. Established in a factorial structure ⌠X 2 = 43; 34 gl; p = .47; NFI = .95; NNFI = 1; CFI = 1 ⌡ those pro-environmental competences explain water savings (R 2 = .54; ξ = .46). |

2002 | Espinosa, Orduña and Corral | They demonstrated, by means of a structural model ⌠X 2 = 271.5; 84 gl; p <.001; NFÍ = .90; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .03 ⌡ that the reasons are indicators (R 1 = .15) of the water saving competences. Also, bathing, washing dishes and brushing teeth are indicators of skills (R 1= .80, R 2 = .85 and R 3 = .24 respectively). They established in a factorial structure ⌠X 2 = 271.5; 84 gl; p <.001; NFÍ = .90; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .03 ⌡ the prediction of water saving competences (β = .32). |

2003 | Corral | Demonstrated in a structural model ⌠X 2 = 249.7; 103 gl; p <.001; IANN = 0.91; IAC = .93; GFI = 1; RQQMEA = .04 ⌡ that washing dishes, watering plants and taking chuveiro bath are indicators of the abilities (R 1 = R 2 = .58, R 3 = .57 and R 4 = .50 respectively). Established in a factorial structure ⌠X 2 = 249.7; 103 gl; p <.001; IANN = 0.91; IAC = .93; GFI = 1; RQQMEA = .04 ⌡ that utilitarianism explains the variability of water consumption (R2 = .22; ξ = .78). He showed, through a structural model, the incidence of domestic utensils on water consumption. In this model, the reasons, scarcity and skills, had a negative effect on water consumption. |

2003 | Corral et al., | With a sample of 200 Mexican residents, they showed that water savings are strongly related (R = 23; p <0> |

2003 | Corral, Bechtel and Fraijo | Demonstrated in a structural model ⌠Model 1: X 2 = 235.1; 111 gl; p <.001; CFI = .92; NNFI = .87; RMSEA = .047 Model 2: X 2 = 528.4; 263 gl; p <.001; NNFI = .90; CFI = .91; RMSEA = .045 ⌡ the direct and indirect effects of general beliefs on water consumption, general beliefs have a direct effect on water consumption. General beliefs have an indirect effect when moderated by utilitarianism. They concluded that the second model better explains the variability of water consumption. |

2003 | Corral, Frías and González | Demonstrated in a structural model ⌠X 2 = 26; 25 gl; p> .05; NNFI = .95; CFI = .96; RMSEA = .02 ⌡ the direct and positive effect (β = .35) of antisocial behavior on the hydrological waste |

2003 | Sainz and Becerra | They reviewed the conflicts reported by the press in 20 years and found a tendency to exacerbate conflicts in demarcations of eastern Mexico City. |

2004 | Narrow and Martinez | With a sample of 209 Spanish inhabitants, they established the direct, negative and significant effect of the exogrupal perception on two dimensions (public and private) of the contact intention (β = -.27; p <.001; β = -.16; p <.001 respectively). |

2004 | Busts | Demonstrated in a structural model ⌠X 2 = 17.17; 13 gl; p> .05; NNFI = .99; RMSEA = .030 ⌡ the incidence of beliefs of obligation to save water on effective abilities (β = .21). In turn, effective skills determine (β = .31) pro-environmental behavior (personal grooming and food preparation). He established that the locus of internal control directly and positively affects the obligation beliefs (β = .37). |

2004 | Bustos et al., | They demonstrated the direct, positive and significant relationship between three pro-environmental behavioral variables; washing of bathrooms with personal hygiene (r = .17; p <01 xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed> |

2004 | Bustos, Flores and Andrade | They established in a structural model ⌠X 2 = .35; 10 gl; p = .000; GFI = .97; AGFI = .92; RMSEA = .08; R 2 = .25 ⌡ the direct, positive and significant effect of the internal control locus on water saving (β = .14) and the indirect effect on three paths; the first through the beliefs of obligation to take care of the water (β = .43) which determine the instrumental abilities (β = .20) and these the water saving (β = .36), the second trajectory through the reasons for socio-environmental protection (β = .21) who influence water saving (β = .14) and the third route through the perception of risk to health (β = .30) that causes the reasons of socio-environmental environmental protection (β = .20). In addition, they established the indirect effect of knowledge through instrumental skills (β = .07) |

2004 | Corral et al., | They established in a structural model ⌠x 2 = 351; 231 gl; p <.001; NNFI = .90; CFI = .91; RMSEA = .04 ⌡ that the present both hedonistic and fatalistic would covary negatively (φ = -.18; φ = -.35) with the saving of water. Likewise, they showed that the propensity to the future also has a close positive relationship (φ = .17) with the endogenous variable of first order. In turn, the propensity for the future had a "phi" relationship with the positive past (φ = .67), with the fatalistic present (φ = .28) and with the hedonistic present (φ = -.28). The negative past with the positive past (φ = .26), with the fatalistic present (φ = .44) and with the hedonistic present (φ = .21). The fatalistic present with the hedonistic present (φ = .65). They established in a structural model ⌠x 2 = 430.6; 271 gl; p = .001; NNFI = .90; CFI = .90; RMSEA = .05 ⌡ that the propensity to the future predicts directly, positively and significantly (β = .40; p <.05) to austerity itself which in turn is also predicted (β = .23; p <.05) by the altruism and predictor (β = .37) of water saving. |

2004 | Corral and Pinheiro | They established in a factorial structure ⌠x 2 = 14.4; 9 gl; p = .10; NNFI = .95, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05 ⌡ than effectiveness (effective reaction in caring for the environment), deliberation (strategy for social, individual and agency welfare), anticipation (contingent plan) which will apply immediately or in the future), solidarity (altruistic reaction towards human beings, animal and plant species) and austerity (form of transformation and minimum consumption of natural resources) are indicators (R 2 = .66, .69, .43, .33, .58, .29 respectively) of sustainable behavior. They established six dimensions of sustainable behavior related to austerity, anticipation, altruism, effectiveness, deliberation and saving. They demonstrated positive and significant associations between the dimensions. Later, in a structural model, they demonstrated the reflectivity of the sustainable behavior around the six dimensions referred to. They established in a factorial structure ⌠x 2 = 14.4; 9 gl; p = .10; NNFI = .95, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05 ⌡ the direct, positive and significant covariances between anticipation with austerity (φ = .48), with altruism (φ = .43), with effectiveness (φ = .23), with the deliberation (φ = .16) and with the reported water saving (φ = .21). this last variable with austerity (φ =, 18), with deliberation (φ = .21) and with effectiveness (φ = .23) who was related to deliberation (φ = .22) and altruism (φ). = .25) which in turn was related to austerity (φ = .36) which was finally related to the deliberation (φ = .16) |

2004 | Fraijo, Tapía y Corral | They showed in a factorial model ⌠X 2 = 479.78; 294 gl; p = .001; NNFI = .91; CFI = .92; RMSEA = .06 ⌡ the direct effect of an intervention on the structure of water saving competencies (β = .98), which includes as indicators the beliefs, the skills, the knowledge and the reasons in order of importance. As a consequence, water saving competencies had a direct, negative and significant effect (β = -.15) on observed and recorded water consumption. Therefore, the environmental education program applied in this sample contributed to a better water saving via competencies. |

2004 | Hernández and Reimel | with a sample of 314 Venezuelan heads of family established the direct, positive and significant causal relationship between four variables in which the participation in a community organization influences the quality of life ( b = .10; p <.05), the type of family housing affects quality of life ( b = .15; p <.05) and participation in a community organization is a determinant of quality of life ( b = .18; p <.001). |

2004 | Medina et al., | with a sample of 169 Spanish workers, they demonstrated the direct, positive and significant effects (β = .20; p <.05) of the task conflict on the supportive climate. They also established the prediction (β = .24; p <.05) of the climate of goals from this conflict. |

2004 | Urbina | He demonstrated that both water pollution and water scarcity are perceived as risks both by non-experts and by experts who objectively assess risks. |

2004 | Valenzuela et al., | They showed in a factorial structure ⌠X 2 = 430.6; 271 gl; p = .001; NNFI = .90; CFI = .90; RMSEA = .05⌡the validity of instruments that measure four psycho-environmental variables; Future propensity (factorial weights of R 1 = .48, R 2 = .63, R 3 = .70, R 4 = .74, R 5= .63, R 6 = .66, R 7 = .70, R 8 = .40, R 9 = .63, R 10 = .67), self-reported water savings (R 11 = .40, R 12 = .64, R 13 = .60, R 14 = .66) , austerity (R 15 = .40, R 16 = .48, R 17 = .37, R 18 = .49, R 19 = .39, R 20 = .22 and R 21 = .65) and altruism (R 22 = .80, R 23 = .73, R 24 = .79 and R 25 = .78). Demonstrated in a factorial model ⌠X 2 = 430.6; 271 gl; p = .001; NNFI = .90; CFI = .90; RMSEA = .05⌡ that the propensity to the future predicts directly, positively and significantly (β = .40) to austerity itself which in turn is also caused (β = .23) by altruism and in turn (β =. 37) saving water by explaining 14% of its variance. |

2005 | Fraj y Martínez | They demonstrated the moderating effect of environmental knowledge on the causal relationship between affective, verbal and real commitment. To the extent that environmental knowledge was minimal, the causal relationship and the percentage of variance were low.In contrast, when the level of environmental knowledge was specialized, the causal relationships and the variance explained increased significantly. |

2005 | Meinhold and Malkus | With a sample of 848 Americans, they established the direct, positive and significant effect of environmental attitudes and environmental knowledge on pro-environmental behavior (β = .44 and β = .26 respectively and with a significance of .01). |

2006 | Becerra et al., | They described the conflicts between authorities and users of the drinking water service in Mexico City and evidenced their transformation from protests to confrontations between neighbors and the police due to roadblocks. |

2006 | Corral y Frías | They showed in a factorial structure ⌠X 2 = 285.5; 203 gl; p <.001; NNFI = .90; CFI = .91; RMSEA = .000 ⌡ the direct effect of normative beliefs and antisocial behavior (β = .22 and β -.18 respectively) on water conservation. |

2008 | Bolzan | He found significant differences between the dimensions of Pro-environmental behavior; recycling, saving, cleaning, activism, consumption and desirability with respect to the type of company. He showed that the values of self-transcendence are the essential determinants of the pro-environmental dimensions of behavior. |

2008 | Corral et al., | They demonstrated five dimensions of water consumption related to the use of basins, showers, irrigation and cleaning. Later, they established through a structural model, the incidence of ecological and utilitarian beliefs about water consumption. Both beliefs correlated negatively. |

2010 | Bizer et al., | The framing effect had an indirect relation to intention. Through the certainty of the source, the styles of coverage and dissemination affected the decisions of the individuals. When comparing the direct relationship with the indirect one, the framing effect seems to have been increased by the mediation of the credibility of the source. |

2010 | Brenner | The actors involved in environmental governance generate contradictory information, since it is their actions that contravene the agreements involved in the administration of common natural resources. |

2010 | Gissi and Soto | The appropriation of the space is made from the tequio that is the personal work done by a member before entering the guatza or community work. |

2010 | Montilla et al., | Cooperativism supposes a human and social system indicated by processes of self-construction, self-production, self-organization and self-poiesis. |

2010 | Sharples | The main source of information on climate change were television news (23.9%), food and beverages with the most consumed by the sample (83.8%), the focus was the most used object to combat the change climatic (88.7%). |

2010 | Wirth et al., | They carried out a study in which they correlated the prominence of media, public and political arguments. They established positive associations between public and political arguments with mediatic arguments at three levels of amplitude; low, medium and high.When comparing media discourses of high and low influence, the authors found that the associations were significant at a single level of intermediate amplitude, neither very high nor very low. That is, the influence of the media on public opinion and political campaigns only becomes significant at a level of intermediate coverage. Those media with wide diffusion or low amplitude did not significantly influence public and political discourses. |

2011 | Flowers and Vine | Established the significant differences between density, activity, studies, income and water use with respect to occasional, systematic and absent water savings. |

2011 | Groshek | He found positive and significant relationships between three media (television, radio and press) with respect to the sociopolitical situation of 122 countries. |

2011 | Marqués et al., | They found a medium level of knowledge regarding general and specific environmental problems in reference to their attitudes and behaviors. |

2011 | Mateu and Rodríguez | With a sample of 139 news items, they demonstrated, through a content analysis, the similarities between national and local contexts around the coverage of a protected area. Such convergences activated the priming of public opinion both nationally and locally. |

2011 | Solis | The sense of environmental responsibility directly, positively and significantly determined the saving of domestic and residential water. The emotional affinity towards the environment affected the residential management of municipal solid waste. |

2012 | Garcia | He demonstrated the agenda effect in the local print media regarding complaints and conflicts in a demarcation with low water availability and high index of informal water trade. |

2012 | Moyo et al., | The perceived cycle of rain was the phenomenon most remembered by farmers (72%), while winter (1%) was the least remembered event. The four seasons were remembered as the phenomena of greatest change (23%), finally, climate change was identified as the main cause of the changes perceived (53%). |

2013 | Corral et al., | They established by means of a structural model [χ 2 = 641.82 (201gl) p <0 xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed xss=removed> |

2013 | Dasaklis and Pappis | The literature reviewed attributes greater relevance to climate change in productive and administrative processes. Mainly in the design of processes and operations that reduce the impact of climate change on the environment. It is an environmental responsibility generated from a green agenda but established from the minimization of operating costs. |

2013 | Garcia | He conducted a search of journalistic sources that covered the conflicts related to the drinking water service in a demarcation of Mexico City and found the prevalence of attributions to the marketocracy. |

2014 | Carreón et al., | They demonstrated that the water conflicts are centered on the forgiveness of payment and the proximity of the local elections as federal in Mexico. They established criteria for analyzing the content of press releases regarding water conflicts linked to local elections and support for parties such as environmental candidates. They specified a model of socio-political agenda for the study of the governance of water resources and services, as well as the measurement of consumption and collection with an increase in tariffs. |

2015 | García et al., | They linked the establishment of the agenda with the governance of the water services in a situation of scarcity and shortage of water reported in the press of national circulation. They demonstrated the tendency of a propaganda in favor of the public administration of water, but a private management in terms of deposits, pumping and distribution. |

2016 | García et al., | The social representations of the workshop consist of sites for collective action, social mobilization and community participation around water supply, consumption and payment of the service. |

2016 | Roman and Cuesta | They reviewed the studies concerning environmental communication and established as central themes; media action, environmental journalism, catastrophism, promotion of pro-environmental behavior, evaluation and planning of communication policies aimed at environmental conservation. |

2018 | Garcia | He reviewed the literature on the governance of water sustainability to highlight co-responsibility as the factor of excellence of co-management, assumed as a dialogue between political and social actors, as well as between public and private sectors. |

2018 | Sandoval, Bustos and García | They demonstrated that the local water sustainability is gestated from the social and political co-participation between authorities and governed with respect to the establishment of tariffs, subsidies and forgiveness. |

Source: García (2018)

Regarding the concepts of governance and ecocity, those of capacity, habitude and spatiality's are proposed. In this sense, the work is inscribed in developmental humanism (freedoms, capacities and responsibilities), structuralist constructivism (habitus, capitals and fields) and Marxist urbanism (spatiality's). These authors propose universal elements around the city and inclusion to sustainability:

Freedoms, capacities and responsibilities for the reappropriation of the city (spaces and water resources).

Habitus, capitals and fields where conflicts are generated by the redistribution of resources and spaces in the city (aquifers, networks and pipes).

Spatiality's for the governance of the local resources of the city (awareness for the equitable distribution of water).

Governance and ecocity would have a more social composition. The proximity of the concepts to the everyday styles, will allow to discuss the importance of the political system of governance in reference to the economic system of ecocity. In this sense, it is necessary to open the debate on social inclusion through the right to a city, mainly to natural resources and essentially to water resources as elements of local sustainable development (Brites, 2012).

The concept ecocide is multidimensional. It has been understood as an economic, political and social system to reduce the ecological footprint of previous generations in reference to the capacities of previous generations, a space limited to one million inhabitants, whose activities are agriculture and industry as a function of water availability, although conflict scenario, recycling is considered as its main development tool (Nacif, Martinet & Espinosa, 2011).

The eco-city concept is related to others of a socio-historical nature. Together with the categories of freedoms, capacities, responsibilities, habitus, capitals, fields and spatiality's, the concepts of governance, segregation, sustainability, centrality, inclusion, periphery and surplus value will make it possible to conceptualize the problem of scarcity, marketcracy and shortage in the demarcation of study (Pérez, 2010).

If the concepts used are considered, a governance system oriented towards the eco-city is opposed to segregation via the relocation of social sectors from the naturalization of their exclusion but is closer to local development since the term sustainability incorporates the system of government as rector of the resources and services of the ecocity. Rather, a governance system is developed in small localities such as the neighborhood or the periphery to extend to the center of the city. This is how the ecocity indicators would be those related to sustainability and inclusion. In this sense, the studies on the sustainability and ecocity projects seem to demonstrate the viability of the terms based on heterogeneous indicators (Nozica, 2011).

Latin American studies on scarcity, marketocracy and public policies on water resources in cities have used various instruments to measure indicators of local water sustainability. The management of water resources; the ethnic appropriation of the urban space; population density as a factor of residential sustainability; national identity as an argument for the design of buildings; the reordering from the inclusion and spatial exclusion, the policies of bi- oceanic peri-urban tourism ; the perception of peri-urban risk; The segregation of public squares and the representation of the city according to social strata are examples of the empirical relevance of studying scarcity, marketocracy and public policies regarding the water resources of Mexico City (Santamaría, 2012).

Empirical studies on sustainability and eco-city have incorporated the symbolic and representational dimension of those who consume resources and therefore evaluate public services. In this way, studies have focused on the impact of public policies on the lifestyles of indigenous peoples, communities, neighborhoods and peri-urban localities in reference to centrality and territorial ordering. In such a process, qualitative studies have replaced the quantification of spaces, instruments such as plans, records and maps have been replaced by in-depth interviews. The investigation of spatial relations and natural resources have now incorporated representations of public services as a fundamental element of the governance system through the establishment of fees for municipal services (Oorostegui & Matos,2009).

The relations of appropriation, transformation and distribution of resources and spaces in their development process, encouraged the differentiation of social classes. As the differences were exacerbated, the segregation of the spaces protected the appropriate and transformative differences at the same time as it enhanced the distributive differences of the resources, mainly the water ones. This process confronted public policies against lifestyles privileging market demands (Iglesias, 2010).

Regarding the situation of scarcity and shortage generated by public policies that adjusted to market demands, marginalized, excluded and vulnerable sectors developed skills, knowledge and strategies for appropriating spaces (aquifers, facilities, networks) to supply and confront the authorities for the regularization of the service. In this framework, the transformation of water resources was delegated to the federal government and the collection of the service to the local government. In this sense, the shortage of water and the increase in tariffs oriented the water conflicts towards the forgiveness of debts, the implementation of meters, the repair of visible leaks, the protection of facilities, the control of demonstrations and agreements between authorities with representatives of the users. In contrast, the concessions of the aquifers, the technology of recycling and fluvial uptake, the investment in infrastructure, the detection of imperceptible leaks, the contamination and overexploitation of the aquifers, the cultures of the water and the real estate deregulation were ignored as problematic that prevent the sustainability of the city (Loyola & Rivas, 2010).

Within the framework of eco-city projects and the evaluation of their governance systems, mainly public policies on natural resources, essentially water resources, the Human Development Index aims to observe, measure and compare freedoms, capacities and responsibilities, but in the best of cases it only records the amount of public goods that would demonstrate local sustainability. Therefore, an index describing sustainability with emphasis on water resources is required, referring to its availability, extraction, distribution, consumption, reuse, recycling and tariff as constituent elements of a local governance system. (Malmod, 2011).

Modeling ecocity

A model is a representation of the themes, the axes, the trajectories and the interrelationships between the factors used in the agenda of the reviewed literature.

The governance of the eco-city is indicated by the opportunities for ecological freedom that state institutions must guarantee for civil society to develop fields of state participation in which agreements will be established. In this process, negotiation and agreement capacities are those indicated for the establishment of co-government, provided that in a framework of social capital of responsibility such consensuses are observed.

The opportunities of ecological freedom are state instances in which the institutions will establish the mechanisms and agreements for the inclusion of the civil proposals, but in opposite case, it is the civil organizations that will have to negotiate those spaces with the institutions.

The fields of state participation imply the opening of the government to civil initiatives, at least as far as the public agenda is concerned. In this sense, the institutions open their spaces to civil organizations and the latter conform to the guidelines of the State, mainly in terms of evaluation, accreditation and certification.

Therefore, negotiation and coordination capacities are the first sphere of interaction between governors and the governed. This is because the preamble for a national agreement is the discussion of the asymmetries between the actors, but this process is based on institutional and organizational criteria, as well as on the observation of international organizations.

Finally, the next natural step in the process in question are the social capitals of responsibility, which refer to the merger of state institutions and civil organizations, an indicator par excellence of cogovernment or governance. In the case of the eco-city, such a hybrid would be oriented towards preserving the nature and quality of public services.

Method

Two exploratory and one confirmatory studies of the factorial structure were carried out with an intentional selection of 135 students (M = 22.1 age SD = 1.3 years and M = 7'452.12 SD = 234.35 monthly income) and 105 users (M = 27.4 SD = 4.5 and M = 9'834.23 SD = 245.46 monthly income) of municipal water services, considering their participation in the electoral training system and the federal elections of 2018

In both phases, the Expected Governance Key (EGE-27) was used, which includes reagents alluding to three factors; perception of state negotiations ("The State will manage water services tariffs with international creditors"); expected consensus ("The State will subsidize water tariffs in vulnerable sectors") and expectations of shared responsibility ("The State will collaborate with international organizations in the microfinance of the water service"). Each item is answered with one of five options ranging from 0 = "not likely" to 5 = "quite likely".

The surveys of the first study were carried out in the facilities of the public university and in the second study they were applied in the federal elections of 2018 before and after the suffrages, previous written guarantee of anonymity, confidentiality and respect for their militancy, preference or political ascription, as well as the non-involvement of the results of the study with the sociopolitical status of the respondents.

The statistical analysis package for social sciences was used, version 15.0 for the processing of information; normality, adequacy, sphericity, reliability, validity, fit and residual.

Results

Table 1 shows the parameters of normal distribution which suggest the multivariate analysis of the structures of relationships between variables.

Table 1. Instrument descriptions

R | M | S | W | K | A | F1 | F2 | F3 |

r1 | 4,37 | 1,01 | 1,89 | 1,65 | ,782 | ,436 |

|

|

r2 | 4,39 | 1,09 | 1,65 | 1,84 | ,761 | ,532 |

|

|

r3 | 4,13 | 1,07 | 1,48 | 1,73 | ,703 | ,640 |

|

|

r4 | 4,05 | 1,09 | 1,34 | 1,54 | ,794 | ,413 |

|

|

r5 | 4,12 | 1,08 | 1,40 | 1,29 | ,785 | ,426 |

|

|

r6 | 4,30 | 1,05 | 1,75 | 1,53 | ,762 | ,395 |

|

|

r7 | 4,56 | 1,05 | 1,69 | 1,27 | ,705 | ,521 |

|

|

r8 | 4,67 | 1,01 | 1,65 | 1,42 | ,761 | ,650 |

|

|

r9 | 4,12 | 1,09 | 1,54 | 1,40 | ,793 | ,652 |

|

|

r10 | 4,39 | 1,06 | 1,36 | 1,62 | ,772 |

| ,549 |

|

r11 | 4,62 | 1,01 | 1,83 | 1,82 | ,752 |

| ,623 |

|

r12 | 4,39 | 1,00 | 1,57 | 1,95 | ,751 |

| ,593 |

|

r13 | 4,14 | 1,08 | 1,93 | 1,71 | ,763 |

| ,612 |

|

r14 | 4,56 | 1,05 | 1,56 | 1,90 | ,759 |

| ,504 |

|

r15 | 4,09 | 1,03 | 1,60 | 1,75 | ,769 |

| ,672 |

|

r16 | 4,87 | 1,02 | 1,62 | 1,59 | ,738 |

| ,560 |

|

r17 | 4,36 | 1,05 | 1,73 | 1,62 | ,752 |

| ,632 |

|

r18 | 4,87 | 1,09 | 1,82 | 1,53 | ,760 |

| ,603 |

|

r19 | 4,7 | 1,06 | 1,80 | 1,50 | ,783 |

|

| ,547 |

r20 | 4,10 | 1,04 | 1,65 | 1,82 | ,761 |

|

| ,532 |

r21 | 4,39 | 1,02 | 1,45 | 1,43 | ,792 |

|

| ,641 |

r22 | 4,12 | 1,07 | 1,56 | 1,24 | ,760 |

|

| ,568 |

r23 | 4,89 | 1,06 | 1,45 | 1,57 | ,745 |

|

| ,640 |

r24 | 4,86 | 1,05 | 1,35 | 1,29 | ,739 |

|

| ,562 |

r25 | 4,76 | 1,03 | 1,39 | 1,18 | ,761 |

|

| ,537 |

r26 | 4,65 | 1,02 | 1,25 | 1,10 | ,772 |

|

| ,561 |

r27 | 4,34 | 1,07 | 1,65 | 1,64 | ,769 |

|

| ,593 |

Source: Elaborated with data study; R = Reactive, M = Mean, S = Standard Deviation, W = Swedness, K = Kurtosis, A = Alpha excluded with data study. Method: Ways Principals, Rotation: Varimax. Adequation and Sphericity ⌠χ2 = 14,23 (24df) p < ,05; KMO = ,762⌡F1 = Negotiations perceived (14% of the total variance explained and alpha ,782), F2 = Agreements expected (11% of the total variance explained and alpha ,760), F3 = Shared responsibilities (7% of the total variance explained and alpha ,765). All items are answered with one of five options on a scale ranging from 0 = "not likely" to 5 = "quite likely".

In a second study, with the purpose of confirming the factorial structure established in the first investigation, the relationship between the variables was estimated (see Table 2).

Table 2. Correlations and covariations

| M | S | F1 | F2 | F3 | F1 | F2 | F3 |

F1 | 23,45 | 14,35 | 1,000 | ,562*** | ,640** | 1,987 | ,532 | ,610 |

F2 | 22,13 | 16,59 |

| 1,000 | ,571** |

| 1,876 | ,632 |

F3 | 25,47 | 16,32 |

|

| 1,000 |

|

| 1,875 |

Source: Elaborated with data study; M = Mean, S = Standard Deviation, F1 = Negotiations perceived, F2 = Agreements expected, F3 = Shared responsibilities: * p < ,01; ** p < ,001; *** p < ,0001

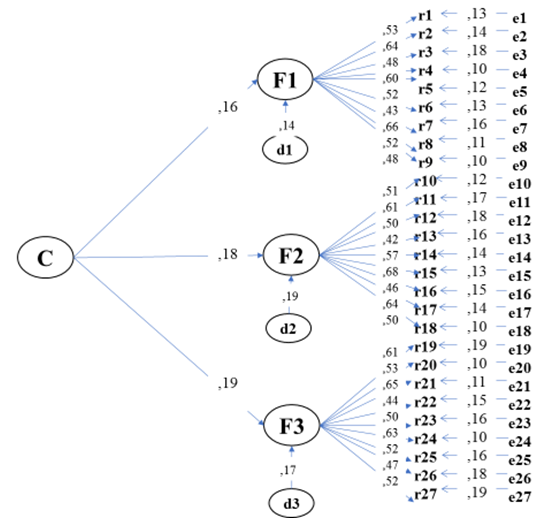

In order to observe the emergence of a second-order factor with respect to the three first-order factors, a structural model was estimated (see Figure 1)

Source: Elaborated with data study; C = Governance; F1 = Negotiations perceived, F2 = Agreements expected, F3 = Shared responsibilities; d = Disturbance measured factor, e = Error measured indicator: ç relations between disturbance or errors and factors or indicators; è relations between factors and indicators

The adjustment and residual parameters ⌠χ2 = 32,12 (23df) p > ,05; CFI = ,990; GFI = ,997; RMSEA = ,0007⌡suggest the non-rejection of the null hypothesis relative to the significant differences between the theoretical relations with respect to the empirical relationships

Discussion

The contribution of this work to the state of the question lies in the complexity of a model for the study of the governance of the ecocity, but by circumscribing the literature to national repositories and the Delphi technique for processing information, these limit the scope from the model to a local context.

Therefore, a search for information in international repositories is recommended in order to process the data with data mining and generate an integral model in which the eco-neighborhood and ecovillage models are recovered, as well as their corresponding theoretical, conceptual and empirical frameworks.

García, Carreón and Quintero (2015) demonstrated two dimensions of sustainability governance related to aversion and propensity to risk and consensus, establishing a second-order factor structure with perceived negotiation. In the present work the expectations of state negotiation have been highlighted as a factor of first order that would explain in 14% the total percentage of variance.

Garcia, Juárez and Bustos (2018) established three dimensions related to agreements between political and social actors with regard to water issues. These are the favorable provisions for the rector of the State, civil participation and co-management. In the present study, the consensus expectations dimension was established to account for the state's management with respect to the international financial institutions that would explain the state's management of public water services.

Bustos, Quintero, García and Aguilar (2018) established two dimensions related to corporate responsibility; image and prestige as concomitant factors to a factor of second order: responsible reputation. In the present investigation, the factor of shared responsibility was established to explain the incidence of civil participation in the sectoral water policy and agenda.

Lines of research concerning perceived governance and its dimensions of expectations of conflict resolution, expected agreements and shared responsibility with respect to factors such as the provisions to the system of government and leadership will allow to explain the differences and similarities between political and social actors, as well as between public and private sectors.

Conclusion

The objective of this work was to confirm the factorial structure of governance expected in the face of contingencies, risks and potential threats of scarcity, shortage, unhealthiness and scarcity of water resources and services, although the design of the research limits the findings to the study scenario, suggesting the extension of the model to other scenarios of building an agenda with in-depth local politics. The relationship between the negotiations of conflicts, agreements and co-responsibilities will make it possible to move towards the establishment of a responsible government in situations of potential risk to local public health.

References

- Bourdieu, P. (2002). Power field, intellectual field. Itinerary of a concept. Buenos Aires: Montressor.

- Brites, W. (2012). The adversities of the habitat in housing complexes of relocated population. Teolinda, B olivar and E razo J. (coord.). Dimensions of the Mexican popular habitat. (pp. 121-142). Quito: CLACSO

- Bustos, J. M., Quintero, M. L., García, C. y Aguilar, J. A. (2018). Gobernanza de la sustentabilidad local: Índices de mediatización hídrica para la Ciudad de México. Tlatemoani, 24, 1-10

- Carreó, J. (2016). Gobernanza y emprendimiento social. México: UNAM.ENTS

- Carreón, J., Hernández, J. & García, C. (2014). Empirical test of an agenda setting model. University Act, 24 (3), 50-62 http://dx.doi.org/10.15174.au.2014.598

- Cravino, M. (2012). To inhabit new neighborhoods of social interest in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires: the space built by the State and lived by the neighbors. In Teolinda, Bolivar & Erazo J. (coord.). Dimensions of the popular Mexican habitat . (pp. 101-120). Quito: CLACSO

- Cueva, S. (2012). The public space as a right to the city. A tour through the heritage of the historic center of Quito. In T eolinda , B olivar and E razo J. (coord.). Dimensions of the Mexican popular habitat. (pp. 267-294). Quito: CLACSO

- García, C. (2013). The knowledge network in a university with a system of professional practices and a technological-administrative social service. Fundamentals in Humanities, 14 (1), 135-157

- García, C., Carreón, J. & Quintero, M. (2016). Contrast of a model of the determinants of the managing personality. Without End, 16, 70-85

- García, C., Carreón, J. & Quintero, M. L. (2015). Dimensiones de gobernanza para la sustentabilidad hídrica. Pueblos y Fronteras, 10 (20), 195-203

- García, C., Carreón, J., Sánchez, A., Sandoval, F. and Morales, M. (2016). Reliability and validity of an instrument that leadership and educational management. Ehquity, 5, 109 -130 DOI: 10.15257 / ehquidad.2016.0004.

- Garcia, C., Juárez, M. & Bustos, J. M. (2018). Specification of a model for the study local governance. Sincronia, 22 (73), 459-472

- Gissi, N. & Soto, P. (2010). From stigmatization to neighborhood pride: Appropriation of space and social integration of the Mixtec population in a colony of Mexico City. INVI. 68, pp. 99-118

- Guillén, A. (20 10). Perspectives on the environment in Venezuela. Notebooks UCAB, 10, pp. 29-55

- Iglesias, Á. (2010). Strategic planning as a public management instrument in local government: case analysis. Cuadernos de Gestión , 10, pp. 101-120

- Lefébvre, H. (1974). The production of space. Australian: Blackwell Publishing.

- Loyola, C. & Rivas, J. (2010). Analysis of sustainability indicators for its application in the city. Time and Space, 25, pp. 1-15

- Malmod , A. (2011). Logic of occupation in the conformation of the territory. Territorial planning as an instrument of planning. Iberoamerican Urbanism Magazine. 6, pp. 18-30

- Molini, F. & S algado , M. (2010). Artificial surface and single-family homes in Spain, within the debate between compact and dispersed city. Bulletin of Association of Spanish Geographers. 54, pp. 125-147

- Nacif, N., Martinet, M. & Espinosa, M. (2011). Between idealization and pragmatism: plans for the reconstruction of the City of San Juan, Argentina. Iberoamerican Urbanism Magazine. 6, pp. 5-17

- Nozica, G. (2011). Plan for territorial integration. The desirable scenarios of insertion of the province of San Juan al Mercosur. Iberoamerican Urbanism Magazine. 6, pp. 43-54

- Oorostegui , K. & Matos, A. (2009). Behavior of the generation of solid domestic waste in the Chaclayo district. Journal of University Research. 1, pp. 44-51

- Pallares, G. (2012). Right to the city: homeless people in the city of Buenos Aires. In T eolinda , B olivar and E razo , J. (coord.). Dimensions of the Mexican popular habitat. (pp. 171-186). Quito: CLACSO

- Paniagua, L. (2012). Urban disputes: space and differentiation in the neighborhood. In Teolinda, Bolivar & Erazo J. (coord.). Dimensions of the Mexican popular habitat . (pp. 245-266). Quito: CLACSO

- Pérez, G. (2010). Financing of urban-ecological projects through the exchange of carbon credits. Urbano. 22, pp. 7-21

- Santamaría, R. (2012). The accreditation of a need for housing as a requirement for the transformation of rural land. Redu, 10, pp. 193-206

- Sen, A. (2011). The idea of justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

- Urquieta, M. & Campillo, C. (2012). The feminine representations of the urban space. New demands for the democratic and inclusive construction of the city. In Teolinda, Bolivar & Erazo J. (coord.).Dimensions of the Mexican popular habitat . (pp. 311-330). Quito: CLACSO

- Verissimo, A. (2012). Program for the regulation and formation of capital gains in informal developments. In Teolinda, Bolivar & Erazo J. (coord.). Dimensions of the Mexican popular habitat . (pp. 45-68). Quito: CLACSO

- Vieira, N. (2012). Popular housing and public security: the process of pacification of the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Teolinda, Bolivar & Erazo J. (coord.). Dimensions of the Mexican popular habitat . (pp. 143-164). Quito: CLACSO