Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-5127/013

Recurrent primary spinal hydatidosis: an exceptional etiology of spinal and radicular compression

1 Radiology Department, Mother-Child Hospital, CHU Mohammed VI, Marrakech, Faculty of Medicine of Marrakech, University Cadi Ayyad

*Corresponding Author: M. Mahir

Citation: M.Mahir, K.Alloula, B.Zouita, D.Basraoui, H.Jalal (2023), Recurrent primary spinal hydatidosis: an exceptional etiology of spinal and radicular compression, Journal of Radiology Research and Diagnostic Imaging.2(3). DOI : 10.58489/2836-5127/013

Copyright: © 2023 M.Mahir, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 26 February 2023 | Accepted: 03 April 2023 | Published: 05 April 2023

Keywords: hydatid cyst; spine; imaging

Abstract

Spinal hydatidosis is an extremely rare occurrence in both children and adults, but it represents the most severe form of bone involvement in echinococcosis. The bone lesions are extensive, with a very progression to neurological complications. Radiologic diagnosis of vertebral hydatidosis, is often difficult. Although surgery is an aggressive treatment therapy for the disease, the recurrent rate remains high. Therefore, it is an imperative management to combine the routine medical imaging with clinical history in the preoperative evaluation and during follow up. We report a case of recurrence of a hydatid cyst with vertebro-medullary localization. The patient underwent 2 operations. We followed up the case for 2 years, thus we discussed our experiences in the diagnosis of spinal hydatidosis.

Introduction

Echinococcosis rarely affects the skeleton. Delays in diagnosis and therapeutic difficulties characterise this disease. To improve the prognosis, early diagnosis with modern imaging is necessary, as well as prevention [1].

Observation

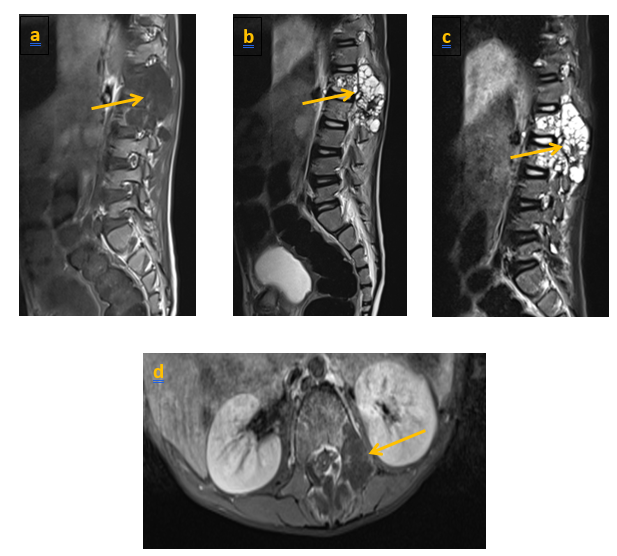

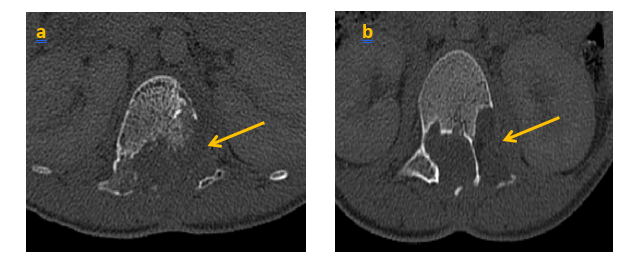

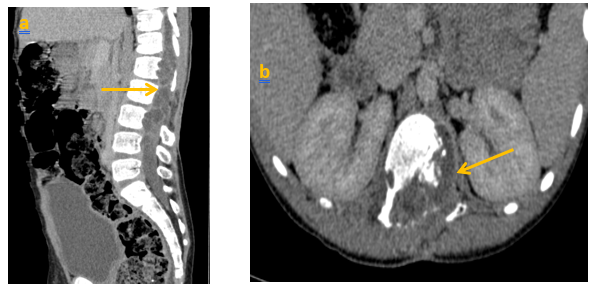

We present the case of a child, aged 8 years, who underwent surgery in 2020 for a lumbar vertebro-medullary hydatid cyst revealed by a cauda equina syndrome, the hydatid serology was positive and the postoperative pathology examination confirmed the diagnosis. One year later the child was admitted with the same clinical symptoms. LIRM objectified multiple variably sized cysts swelling in paraspinal area of T12-L2 levels and the cyst walls were slightly enhanced. There were neither clear bound- aries between the cysts and surrounding tissues, nor evidence of spinal cord compression (figure 1) the patient underwent surgery again. Currently, he is consulting for a dorsolumbar spinal syndrome with sphincter disorders. Clinical examination found a 4/5 motor deficit in both lower limbs. A dorsolumbar CT scan confirmed bone lysis of the posterior walls of L2, L3 and L4, extended to the left pedicle of L2. In the parenchymal window, the intracanal extension of the multiloculated cystic lesions is evident, giving a grape-like appearance, with walls and partitions discreetly enhanced by PDC. They exert a mass effect on the medullary cord and the nerve roots in front of it (Figure 2, 3). In view of the patient's history, the diagnosis of a recurrence is evoked. The extension workup for other hydatid sites was negative. The patient was operated on. The most complete possible evacuation of the hydatid vesicles, associated with a careful curettage, was performed. Hydatid serology was positive. Albendazole was prescribed, with clinical and serological monitoring.

Discussion

Hydatidosis is an anthropozoonosis due to the development of the larval form of Echinococcus granulosus [1]. The disease principally occurs in dogs, wolves, foxes, sheep, mice, horses. Humans are only accidental intermediate hosts, and cannot transmit the disease [2]. The infestation starts with ingestion of the eggs of the adult tapeworm. The larvae are released in the duodenum, cross the wall and pass from the portal system to the liver [1]. Notably, hydatidosis infection in humans mainly occurs in the liver and lungs, and the disease has a very long period of asymptomatic incubation until hydatid cysts grow to an extent that results clinical symptoms [2]. Bone involvement is rare: 0.5-2.5% of all hydatid cases [1]. Spinal involvement involves the vertebral bodies, which are drained by porto-vertebral shunts. The dorsal spine is the most frequently affected (80%). This is followed by the lumbar spine (18%) and the cervical spine (1%) [3]. It is an insidious disease, with non-specific clinical signs: pain, local soft tissue swelling, pathological fracture [4]. Neurological damage occurs progressively, the classical presentation is spinal cord compression. Moreover, several retrospective studies have reported the rate of medullary compression in case of spine hydatidosis ranges between 47% and 73% [2].

Hydatid serology is often negative, becoming positive only at the stage of soft tissue invasion [3, 5]. Diagnosis of hydatidosis not only depends on serological examinations, but also on radiology and biology. Certainly, histopathological diagnosis is the gold standard [2]. The radiological appearance is not specific. Initially, it consists of multiple localised lacunae, which gradually become confluent, creating a grape-like appearance [1]. Costovertebral involvement is suggestive of the diagnosis. Although CT can be used to assess bony involvement, it is not suitable for identification of soft tissue components. Notably, MRI is the pre ferred imaging technique for diagnosis of spinal hydatidosis. They also allow prolonged monitoring. On MRI, hydatid vesicles, in their typical forms, appear in hyposignal T1 and hypersignal T2 [1]. The recurrent lesion was larger and more significant than previous results from enhanced MRI. We attributed the difference to bone destruction or disease progression, in addition to the formation of scar tissue after the operation [2]. The differential diagnosis may include tuberculous spondylodiscitis, metastases and aneurysmal cyst. The treatment of spinal hydatidosis is surgical. The role of medical treatment is not negligible for some authors. It seems to improve the painful symptomatology. It has its place especially in inoperable forms and also as an adjuvant therapy to surgical treatment [1]. The prognosis is unpredictable, with a five-year survival rate of approximately 50%, due to the high frequency of recurrence and neurological damage. This poor prognosis is related to the often incomplete surgical excision [1] and because of the absence of anatomical features and the existence of neural structures [2]. In the present case, our patient had undergone 2 previous surgery. The best treatment remains prevention of this disease [1].

Conclusion

The spinal location of hydatid cysts is rare and has a poor prognosis. It is characterised by a non-specific clinical symptomatology and a slow but inevitable evolution towards medullary or radicular compression. The prognosis can be improved by early diagnosis using modern imaging techniques (CT, MRI) and, above all, by the implementation of preventive measures, follow up is also needed to detect and take care of any potential recurrence.

References

- A. Hommadi, J. Mounach, T. Ziadi, L. Amhaji, S.M. Drissi. Et.al, (2008) : une étiologie exceptionnelle de compression médullaire et radiculaire. La Lettre du Rhumatologue - n° 339 - février

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Xin Xu, MD, Jiancang Cao, MD, Jiabing Wang, MD ( 2 0 2 2 ). A rare case of recurrent primary dumbbell-shaped spinal hydatidosis. R a d i o l o g y Cas e R e p o r t s 1 7: 3 2 2 4 – 3 2 2 7.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Abdelmoula Cheikhrouhou L, Amira C, Chaabouni L, Ben Hadj Yahia C, Montacer Kchir M, (2005). [Vertebral hydatidosis: medical imaging and management. A case report]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot ;98 :114-7.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Akhadar A, Gourinda H, El Alami Z, Miri A. Kyste hydatique du sacrum: à propos d’un cas. Rev Rhum 1999; 66:331-3.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Karray S, Zlitni M, Fowles JV, Zouari O, Slimane N, et.al (1990). Vertebral hydatidosis and paraplegia. J Bone Surg 72: B84-8

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar