Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-8657/007

Exploratory Model of Commuting Habits in the Covid-19 Era

- Cruz García Lirios 1

- José Marcos Bustos Aguayo2 2

- Miguel Bautista Miranda 2

- Javier Carreón Guillén 2

1.Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México

2.Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

*Corresponding Author: Cruz García Lirios

Citation: Cruz García Lirios, José Marcos Bustos Aguayo, Miguel Bautista Miranda, Javier Carreón Guillén (2023). Exploratory Model of Commuting Habits in The Covid-19 Era. Journal of Surgery and Postoperative Care. 2(1). DOI: 10.58489/2836-8657/007

Copyright: © 2023 Cruz García Lirios, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 04 February 2023 | Accepted: 10 February 2023 | Published: 20 February 2023

Keywords: Habitus, transportation, suburban, city, security

Abstract

A habitus is an unfavorable or favorable disposition towards a risk. In the case of the pandemic, the habitus of transfer and stay suggests contexts that the present work addresses in order to count them with the observations of a sample of students. A cross-sectional study was carried out with 100 students, considering their follow-up of the pandemic and decision to vacation. A structure of five factors was found that explained the effects of state communication on the use of public transport. It is hoped that the proposed model can be extended to the dimensions of the habitus.

Introduction

Until August 2022, the pandemic has claimed the lives of four million people in the world and one million in Mexico, although under-registrations are recognized that could increase the figure (Bustos et al., 2021). In this context of risk, the mitigation and containment policies of the Covid- 19 have focused on the strategies of distancing and confinement, but only in the first months, since at least the communication and management of the crisis has been only the recommendation of healthy distance. This strategy is related to habitus if it is translated as negotiation, agreement and co-responsibility between the parties involved.

A communication of the pandemic that promotes distancing involves the mass transportation system (Quiroz et al., 2020). On the one hand, it impacts on the user's decisions to reduce their mobility. On the other hand, it schedules its decisions based on costs and benefits. The transport user can take the risk of traveling on the public system, although he can calculate the differences with respect to a motor transport. Or, the user chooses to suppress their mobility plans, even when working or studying.

In either scenario, the decision is prospective. That is, the costs outweigh the benefits, but it is these risks that generate the most profits if they are repeated. In this way, prolonged negotiation, consensus and responsibility are associated with irregular communication of risks (Salvatore, 2020). In the case of the government of Mexico, its communication can be considered irregular if the statements of its president and health officials are considered (Casilli, 2019). Until May 2020, the Mexican State presumed that it had controlled the pandemic, but unintentionally the cases increased in June.

However, the citizenry refrained from transporting and vacationing. It was until the end of December when the pandemic reached its peak of contagion, but the hope of vaccines was the government's message (Chapain & Sagot, 2019). The public reacted with a mobility just above the average of previous years. In this period, the habitus or negotiation between the parties was observable in the agglomeration in foreign transport centers. Also, in the provision of food or solidarity such as courtesy trips in taxis. The use of the mobile to stay informed was another indicator, as well as the commitment to wear a face mask.

In this way, a provision in favor of mass transportation emerged. At the same time, there was an underlying agreement between users and authorities to respect the boarding and descent of collective transport (Aspilla et al., 2016). In the same vein, research on the impact of the pandemic on mass transportation suggests that space determines the probability of contagion. This is so because the ventilation in the transport explains the cases of contagion in regular users of the subway.

In the case of tourist transport, the image of the destination, as is the case of biosecurity, is the predictor of the decision to transfer (Nava & Mercado, 2019). Personnel training is another factor that refers to biosecurity as an added value of accommodation. The sum of both biosafety and training protocols affects the tourist's stay, but it is the transfer time and the quality of the service that define the destination.

The habitus is a negotiation between the parties interested in their relationships of symbolic equity (Sanchez et al., 2022). It is an exchange of imaginaries and representations around a social process. In the case of public transport, the habitus is seen in the relationship between supply and demand for transportation. Thus, those who choose a high-risk option such as bus crossings on secondary highways reflect a propensity for risk. In contrast, those who choose a transfer from an airplane are inclined by an aversion to risks (Aldana et al., 2021). Consequently, the determinants of risk aversion or propensity emerge from a balance between costs and benefits of relocation. That is, those who move to a tourist destination, choose their type of transfer according to a profit and loss calculation (Hernandez et al., 2021). This is how those who choose a high-risk transport expect high benefits. In contrast, those who select safer and less risky transportation anticipate a low profit scenario.

The habits of relocation, being conditioned by this logic of costs and benefits, reach a decision process that seeks a balance between the demands of the environment and the internal resources available (Garcia et al., 2021). This is so because tourism is a phenomenon of decisions that involve losses and gains. In the case of choosing a tourist destination, the transfer is a determining factor (Bustos et al., 2020). If the travel habits are sustained from an aversion to risk, the choice of the tourist destination will be repeated systematically (Sandoval et al., 2021). On the contrary, if the travel habits correspond to a propensity to risk, then the selected tourist destination will vary according to the balance between costs and benefits.

Within the framework of the habitus of aversion or propensity to the risk of transfer, the time of transfer is a determining factor in the choice of the tourist destination and its unsystematic or systematic repetition (Garcia, 2021). If the transfer is risk-averse and the transfer time is long, the choice of tourist destination will probably not be repeated (Garcia et al., 2020). The short travel time is related to the habitus of risk aversion in the probable choice of a tourist destination (Molina et al., 2021). Regarding the propensity to risk, both travel times, short or long, affect the non-repetition of a destination.

Based on the theory of the transfer habitus, studies on the matter have established four dimensions: aesthesis, ethos, eidos and hexis (Garza et al., 2021). The aesthetic transfer habitus (aesthesis) correspond to the choice of cultural tourist destinations (Carreon et al., 2020). In the selection of a tourist destination, the logical transfer habitus (eidos) are associated with the offer of science and technology (Guillen et al., 2021). The ceremonial and religious centers are associated with the ethical transfer habitus (ethos). In his case, the preferences for moving to creative cities are determined by habitus of expressiveness (hexis).

The development of instruments that measure travel habits based on the aesthetic, logical, ethical or expressive appeal of a destination made it possible to diversify explanatory models (Perez et al., 2021). These are the cases of the variables of agglomeration, food, civility, connectivity and commitment of tourist services as added values to the image of the destination. The agglomeration had already been proposed as a determining factor of the habitus of transport and the aversion to risks in collective transport (Juarez et al., 2020). In cases where the transfer is prolonged, the food service and the Internet are determining factors in the choice of the type of transport and destination. In cases of risk prevention due to Covid-19, civility is a factor that determines the choice of a transport with proximity (Quintero et al., 2021). Finally, when users identify the transport driver as an expert and responsible, they approach risk aversion.

A model is a strategic representation of the contrast between the findings reported in the literature regarding proposals to address a problem in the case of the image of the destination as a variable determined by the context, type and time of transport and transfer, the model includes the possible relationships between the categories (Alvarado et al., 2021). In this way, the hypotheses that support the contrast of the model warn that the context of transfer: agglomeration, food, civility, cyber use and commitment is different in samples that present habitus of aversion and risk propensity. Consequently, the relationship between the variables of the transfer context will determine the choice of the type of transport and tourist destination (Quiroz et al., 2020). This is so because the context of transfer is a stay that competes with the type of destination. Even the context of transfer is an added value of the image of the destination (Rincon et al., 2021). These are expectations of the journey, stay and return that the user of transport and tourism services add to the image of the destination.

The objective of the work was to explore the factors derived from the communicative habitus in the literature from 2019 to 2022 with respect to the criteria of a sample of students from central Mexico.

Are there significant differences between the dimensions of agglomeration, feeding, civility, cyber use and commitment around tourist mobility with respect to the observations made in the present work?

The premises that guide the present work suggest that there are differences between the dimensions reported in the literature regarding the observations. This is so because the Mexican government's risk communication has fostered a tourist habitus that lies in negotiation, agreements and co-responsibilities. These are the cases of tourists who, before the recommendation of distancing and confinement, congregate in mass transport (Sapiro, 2019). Or, the cases where the State disseminates the supply of resources, but users look for food outside their nearby shopping center. In the same way, in the face of distancing recommendations, users give up their place or taxi drivers offer their services at no cost. All these indicators converge in a provision against or in favor of the management of the pandemic reveal a structure. Such relationships between indicators and factors would explain the effect of pandemic communication on transfer decisions for recreational purposes.

Method

Design. A non-experimental, exploratory and cross-sectional study was carried out. Studies that explain the effect of the media on decision-making and behavior have focused on the establishment of an agenda. It is about establishing the axes and themes related to a theme that is disseminated by the media to influence public opinion (Bedolla et al., 2016). The contrast of this agenda with the habitus would allow anticipating a scenario of impact. In the case of public transport, risk communication by establishing distance and confinement as axes, generated a transversal axis. As risks intensify, transport users create crowds. Thus, cross-sectional measurement is relevant.

Sample. Is one performed nonprobability lesson 100 students (M = 20 years old, DE = 0.36). The inclusion criterion dealt with the journey in hours from home to school (M = 2.46 hrs and SD = 0.30 minutes). Return from the campus to the house (M = 2.00 hrs and SD = 0.70 minutes). The inclusion criteria were to have monitored the presidential conferences on the coronavirus, as well as to have listened to the strategies of distancing and confining people. The use of public transport to vacation, even when they have access to motor transport. In the case of income, factor for choice of destination, the average was 1,781.89 USD per month.

Instrument. Inventory of Habitus Mobility Peri-urban which contains 30 indicators have five response options ranging from "not similar my situation" until "is very similar to my situation". The first version suggests four dimensions allusive to the break, the journey, stay and return, but being general they did not sufficiently explain decision-making. More recent the version of aesthesis (aesthetics), ethos (ethics), hexis (logic) and eidos (expression) obtained greater consistency, but its generality could not anticipate the transfer choices. Both versions reached consistencies higher than the essential minimums, but when they were associated as determining factors of the transfer decision (Olague et a., 2017). Therefore, the exploration of dimensions relative to habitus as negotiation will allow the phenomenon to be explained.

Procedure. Through a telephone contact with the selected sample in which an interview was requested and whose purposes would be merely academic and institutional follow-up to the graduates, whether they were graduates or not. Once the appointment was established, a questionnaire was provided that included the sociodemographic, economic and organizational psychological questions. In the cases in which there was a tendency towards the same answer option or the absence of answer, they were asked to write down on the back the reasons why they answered with the same answer option or, where appropriate, the absence of them. The data were captured in the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) and the analysis of structural equations was estimated with the help of the Analysis of Structural Moments (AMOS) program and the Relationships program. Linear Structural (LISREL).

Analysis. The establishment of the structural model of reflective relationships was carried out considering the normality, reliability and validity of the scale that measured the psychological construct. The kurtosis parameter was used to establish the normality of the distribution of responses to the level of compromise questioned. The results show that the kurtosis parameter had a value less than eight, which is the minimum suggested to assume the normality of the distribution. In the case of reliability, Cronbach's alpha value allowed establishing the relationship between each question and the scale. A value greater than 0.70 was considered as evidence of internal consistency. Finally, the exploratory factor analysis of main axes and pro max rotation in which factorial weights greater than 0.300 allowed the emergence of commitment to be deduced from eight indicators.

Results

Table 1 shows the normal distribution values that suggest a factor analysis. That is, the consistency of the instrument can be observed in other samples. In addition, it refers to five dimensions related to crowds, food, civility, cyber use and loyalty to transport. That is to say, the habitus as dispositions of transfer before the news of the pandemic are configured by the five established factors.

R | Indicator | M | SD | K | α |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 |

r1 | I often get caught up in so many people on the subway | 3.45 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.701 |

| 0.374 |

|

|

|

|

r2 | I try to get on the minibus, even if it reaches its maximum capacity | 3.47 | 0.83 | 1.06 | 0.732 |

| 0.384 |

|

|

|

|

r3 | I use zero-emission transport, even if it circulates at maximum capacity | 3.29 | 0.81 | 1.46 | 0.705 |

| 0.389 |

|

|

|

|

r4 | I share the taxi with the people who can fit | 3.05 | 0.96 | 1.36 | 0.793 |

| 0.301 |

|

|

|

|

r5 | I often go eating on my way to my destination | 3.85 | 0.74 | 1.67 | 0.739 |

| 0.304 |

|

|

|

|

r6 | I try to buy a product to eat on the minibus | 307 | 0.95 | 1.38 | 0.705 |

| 0.394 |

|

|

|

|

r7 | I eat food while sitting on the bus | 3.71 | 0.85 | 1.06 | 0.738 |

|

| 0.312 |

|

|

|

r8 | When transport allows sale, I usually buy something to eat | 3.72 | 0.96 | 1.36 | 0.752 |

|

| 0.385 |

|

|

|

r9 | I usually respect spaces confined to people with different capacities | 3.00 | 0.39 | 1.25 | 0.753 |

|

| 0.391 |

|

|

|

r10 | I avoid invading senior citizens' seats | 3.08 | 0.84 | 1.22 | 0.729 |

|

| 0.384 |

|

|

|

r11 | I collaborate in the identification of missing people in the subway | 3.04 | 0.59 | 1.25 | 0.715 |

|

| 0.336 |

|

|

|

r12 | I help people who ask me for help to reach their destination | 3.01 | 0.51 | 1.63 | 0.703 |

|

| 0.316 |

|

|

|

r13 | When I observe that someone of the third age is standing, I usually offer them my seat | 3.49 | 0.48 | 1.68 | 0.739 |

|

|

| 0.388 |

|

|

r14 | In the subway I usually make sure that the seats for the elderly are respected | 3.36 | 0.36 | 1.47 | 0.734 |

|

|

| 0.345 |

|

|

r15 | I avoid boarding the transport confined to women | 3.14 | 0.85 | 1.49 | 0.704 |

|

|

| 0.315 |

|

|

r16 | I usually pay for transportation to people who ask for help | 3.26 | 0.94 | 1.07 | 0.772 |

|

|

| 0.367 |

|

|

r17 | I check my email while I arrive at my destination | 3.15 | 0.25 | 1.77 | 0.712 |

|

|

| 0.376 |

|

|

r18 | I use the metro network to check my emails | 3.04 | 0.36 | 1.68 | 0.735 |

|

|

| 0.366 |

|

|

r19 | I participate as an Internet user advisor in the metro | 3.72 | 0.46 | 1.49 | 0.789 |

|

|

|

| 0.341 |

|

r20 | I make sure that the cyber users of the subway respect the allotted time | 3.26 | 0.61 | 1.99 | 0.793 |

|

|

|

| 0.346 |

|

r21 | I've waited for the subway until I find a free seat | 3.49 | 0.58 | 1.08 | 0.734 |

|

|

|

| 0.342 |

|

r22 | I've taken the bus from your base to your destination | 3.05 | 0.84 | 1.32 | 0.715 |

|

|

|

| 0.326 |

|

r23 | I have ridden the minibus late into the night | 3.84 | 0.91 | 1.64 | 0.725 |

|

|

|

| 0.346 |

|

r24 | I have waited for public transport before it starts to circulate | 3.31 | 0.88 | 1.57 | 0.730 |

|

|

|

| 0.332 |

|

r25 | While I ride the subway, I review my class notes | 3.20 | 0.95 | 1.42 | 0.748 |

|

|

|

|

| 0.326 |

r26 | I prepare for exams on the way to school | 3.22 | 0.89 | 1.55 | 0.778 |

|

|

|

|

| 0.384 |

r27 | I do my homework while on the subway | 3.04 | 0.97 | 1.23 | 0.792 |

|

|

|

|

| 0.331 |

r28 | I do schoolwork during my ride on the minibus | 3.64 | 0.95 | 1.25 | 0.736 |

|

|

|

|

| 0.368 |

r29 | My sense of punctuality forces me to take different routes to be on time | 3.46 | 0.89 | 1.36 | 0.715 |

|

|

|

|

| 0.346 |

r30 | My schedule of activities allows me to travel on different routes | 3.15 | 0.88 | 1.35 | 0.782 |

|

|

|

|

| 0.306 |

Source: Elaborated with data study; M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, A = Alpha value excluded value item, K = 1.294; Bootstrap = 0.000; F1 = Agglomeration (28% of the variance, alpha = 0.721), F2 = Feeding (25% of the variance, alpha = 0.739), F3 = Civility (23% of the variance, alpha = 0.758), F4 = Cyberuses (14% of the variance, alpha = 0.794), F5 = Commitments (10% of the variance, alpha = 0.745). KMO = 0.682; [X 2 = 14.25 (12gl) p = 0.000]

Once the structure of factors and indicators that explained habitus as a negotiation between political and civil actors had been established, we proceeded to estimate the relationships between these factors in order to observe a common agenda (see Table 2). This is so because the convergence of the five factors would allow us to appreciate the configuration of a structure of themes. This is the case of the communication of the pandemic and its influence on transfer decisions in the surveyed sample.

Table 2. Covariance relationships between factors

| M | SD | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 |

F1 | 24,32 | 13,24 | 1,000 |

|

|

|

| 0.916 |

|

|

|

|

F2 | 22,45 | 15,46 | ,432* | 1,000 |

|

|

| 0.555 | 0.906 |

|

|

|

F3 | 21,26 | 18,43 | ,325** | ,431*** | 1,000 |

|

| 0.000 | 0.676 | 0.991 |

|

|

F4 | 20,43 | 14,35 | ,542* | ,326* | ,438* | 1,000 |

| 0.098 | 0.104 | 0.170 | 0.995 |

|

F5 | 25,47 | 16,20 | ,439*** | ,437* | ,541* | ,631* | 1,000 | 0.125 | 0.252 | 0.328 | 0.005 | 0.903 |

Source: Elaborated with data study; F1 = Agglomeration, F2 = Feeding, F3 = Civility, F4 = Cyberuses, F5 = Commitments; * p < ,01; ** p < ,001; *** p < ,0001

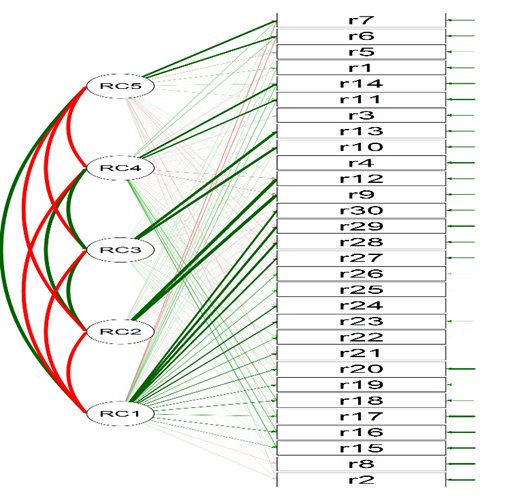

The factor structure suggests a more complex structure with these five factors and thirty indicators. Both make up a tourist habitus as a provision in the face of the pandemic. Consequently, in the face of tourism promotion policies, but with a recommendation of distancing, the surveyed sample tends to decide to agglomerate. This means that risk communication creates counterproductive provisions. In order to corroborate the assumption of differences between the theoretical factors with respect to the exposed findings, a model was contrasted (see Figure 1). This exercise made it possible to establish the agenda as a scenario of risks and habitus. It then means that transport is a space of disobedience because the exhibition exposes more crowds than needs for food, civility, navigation or commitment.

Source: elaborated with data study; F1 = Agglomeration, F2 = Feeding, F3 = Civility, F4 = Cyberuses, F5 = Commitments; R = Indicator, e = Error measurement indicator, ç relation between error and indicator, è relation between factor and indicator, çè relation between factor.

The adjustment and residual parameters ⌠χ2 = 12,23 (13 df) p > ,05; GFI = ,990; CFI = ,997; RMSEA = ,007⌡suggest the non-rejection of the null hypothesis. In other words, the differences between the dimensions reported in the literature and the study findings seem to coincide in a common agenda. This is so because risk communication has such coverage that it fosters hopelessness. In other words, if the State only recommends distancing, confinement or the use of masks without having sufficient detection tests, treatments or vaccines, then the surveyed sample responds with an intention to crowd before the holidays.

Discussion

The contribution of this work to the state of the question lies in the measurement of the habitus before the communication of the pandemic. It is a model of five factors and thirty indicators. It is a structure that suggests a probable agglomeration in the face of distancing and confinement. In this sense, it is advisable to consider habitus as dispositions to agglomeration. This social disobedience in the face of the communication of the pandemic is the beginning of a State-society relationship (Gauna, 2017). The literature has reported the formation of these habitus as responses to the distance and confinement promoted.

This is the case of the stigma before carriers of Covid-19. The State suggests distancing but given the social stigma of doctors as carriers of the coronavirus, it is opaque. This means that the pandemic generates an inconsistent strategy. The effect of this policy on tourism is ambivalent (Khasimah, 2016). On the one hand, it generates hopelessness, but at the same time, it encourages exposure to risks. Given that governments follow the protocol of confinement and distancing, this work will contribute to the modification of such strategy.

Before the pandemic, the prediction of the tourist destination was established from its image. If a tourist selected a place, then it was documented about it. The arrival of the coronavirus changed that pattern. Now, biosecurity is a determining factor in the image of the destination. The tourist chooses from the publicity regarding sanitation. Such biosecurity would not be possible without the habitus of the tourist (Martinez, 2017). Provisions in favor of sanitation would explain the choice of accommodation.

Conclusion

The objective of this work was to compare the dimensions of the habitus in the face of the pandemic. Five factors found explain the social disobedience before the communication of the pandemic. The surveyed sample presented a habitus that consists of the disposition before the coronavirus and their vacations. These are provisions for agglomeration, nutrition, civility, cyber use, and engagement. Each factor explains the habitus that emerges from the spread of confinement and distancing, as well as preventive measures. This is so because the surveyed sample systematically disobeys the promotion of tourism based on contagion risks.

In relation to the theory of the habitus of transfer, which highlights the relationship between aversion or propensity to risk with respect to the choice of destination, the present work warns that the context of transfer is made up of five preponderant factors. In this sense, the differences between the structure of findings reported in the literature with respect to the established model explain the importance of the context of transfer. Research lines related to the context of the stay and return will allow anticipating scenarios of aversion and propensity to risk around the choice of a transport and destination preference.

Regarding the studies of the habitus of transfer where four dimensions concerning expressiveness, logic, aesthetics and ethics stand out, the present work warns that a structure of the context of transfer can be explanatory of the differences between these dimensions. It is a context in which the thoric dimensions become relevant considering the effects of Covid-9 on the decisions of transfer, stay and return of tourists. Therefore, the investigations oriented towards the empirical demonstration of the transfer dimensions will complement the results of the present study where the structure of the transfer context was established. Both issues, context and dimensions of transfer will allow us to explain and anticipate scenarios of aversion or propensity to risk before the decisions of stay and return.

Regarding the empirical test of the modeling of the transport context, where the relationships between the factors of agglomeration, food, civility, Cyberuses and commitment are highlighted as determinants of the type of destination, the present work suggests that the context indicators can anticipate the type of destination. of transfer. This is so because the relationship between the type of transfer and the image of the destination is in the making. Therefore, the context of transfer can contribute to predicting future destination choices, considering the reason for the stay. Studies related to the relationship between the determinants of the transfer and the stay will make it possible to generate biosafety policies that prevent risk scenarios.

References

- Aldana, W. I., Sanchez, R. & Garcia, C. (2020). La estructura de la percepción de la inseguriad pública. Tlatemoani, 34 (1), 52-67

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Alvarado, S., Carreon, J. & Garcia, C. (2021). Modelling of the mobility habitus in the public transport system with low CO2 emissions mechanics in the center of Mexico. Advances in Mechanics, 9 (2), 82-95

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Aspilla, Y., Garcia, F. y Silva, M. R. (2016). Educación para la movilidad no motorizada: sistema universitario del préstamo de bicicletas en la movilidad interior. Ciencias de la Educación, 26 (48), 13-39

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Bedoya, R., Marquet, V., Miralles, O. (2016). Estimaciones de las emisiones de CO2 desde la perspectiva de la demanda de transporte en Medellin. Revista Transporte y Territorio, 15 (1), 302-322

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Bustos, J. M., Juárez, M. y García, C. (2021). Validity if habitus model of coffee entrepreneurship. Summa, 3 (1), 1-21. 6.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Bustos, J. M., Juarez, M., Garcia, C., Sandoval, F. R. & Amemiya, M. (2020). Determinantes psicosociales de la reactivación del turismo en la era Covid-19. Tlatemoani, 28 (1), 1-23

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Carreon, J., Bustos, J. M., Bermudez, G., Espinoza, F. & Garcia, C. (2020). Actitudes hacia la panemia ocasionada por el coronavirus SARS CoV-2 y la Covid-19. Invurnus, 15 (2), 12-16

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Casilli, A. (2019). En la trastienda de la inteligencia artificial. Una investigación sobre las plataformas de micro trabajo en Francia. Arxus, 45, 85-108

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Chapain, C. y Sagot, D. (2020). Cultural and creative clusters a systematic literature review and renewed research agenda. Urban Research & Practice, 13 (3), 300-329

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Garcia, C. (2021). Modelamiento del compromiso laboral ante la Covid-19 en un hospital público del centro de Mexico. Gaceta Medica, 44 (1), 34-40

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Garcia, C., Espinoza, F., Bustos, J. M., Juarez, M. & Sandoval, F. R. (2021). Perceptions about entrepreneurship in the Covid-19 era. Razon Critica, 12 (1), 1-12

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Garcia, C., Juarez, M., Bustos, J. M., Sandoval F. R. & Quiroz, C. Y. (2020). Specification a model for study of perceived risk. Reget, 24 (43), 2-10

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Garza, J. A., Hernandez, T. J., Carreon, J., Espinoza, F. & Garcia, C. (2021). Contrastofa model determinant of tpurism stay in the Covid-19 era: Implications for biosafety. Turismo & Patrimonio, 16 (1), 11-21

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Gauna, C. (2017). Percepción de la problemática asociada al turismo y el interés por participar de la población: caso Puerto Vallarta. El periplo Sustentable, 33 (1), 251-290

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Guillen, J., Bustos, J. M., Valdés, J., Quintero, M. L., Garza, J. A., Morales, F. & Garcia, C. (2021). Modelling of perception Covid-19 era. Virology & Immunology Journal, 5 (1), 1-8

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Hernandez, T. J., Carreon, J. & Garcia, C. (2021). Reingeneering in the entrepreneurship of the coffee industry and tourism in central Mexico. Journal Advances, 9 (2), 63-81

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Juarez, M., Bustos, J. M., Carreon, J. & Garcia, C. (2020). La percepción de riesgos en estudiantes universitarios ante la propagación del coronavirus SARS CoV-2 y la enfermedad Covid-19. Revista de Psicología, 8 (17), 94-108

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Khasimah, N. & Hashim, S., Mohd, S. T. & Harudin, S. (2016). Tourism satisfaction with a destination: An investigation of visitor of Lanwaky Island. Tourism Journal of Marketing Studies, 8 (3), 173-189

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Martínez, J. C. (2017). El habitus una revisión analítica. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 75 (3), 1-14

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - 20. Molina, M. R., Coronado, O., Garcia, C. & Quiroz, C. Y. (2021). Contrast a model of security perception in the Covid-19 era. Journal of Community Medicine & Public Health Care, 8 (1), 77-83

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Nava, M. & Mercado, A. (2019). Redes de gobernanza en el cluster turístico de Mazatlán. Región y Sociedad, 31 (1), 1-22

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Olague J. T., Flores, C. A. & Garza, J. B. (2017). El efecto de la motivación del viaje sobre la satisfacción del turista a través de las dimensiones de la imagen de destino. El caso del turismo urbano de ocio a Monterrey, México. Revista de Investigaciones Turísticas, 14 (1), 119-129

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Perez, M. I., Bustos, J. M., Juarez, M. & Garcia, C. (2021). Actitudes hacia los efectos de Covid-19 en el medio ambiente. Revista Psicología, 10 (20), 9-30

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Quintero, M. L., Nava, S., Limon, G. A., Velez, S. S. & Garcia, C. (2021). Wellbeing subjective in the Covid-19 era. South Asian Journal of Social Studies, 1 (1), 38-49

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Quiroz, C. Y., Bustos, J. M., Juarez, M., Bolivar, E. & Garcia, C. (2020). Exploratory factor structural model of perception mobility bikeways. Propositos & Representaciones, 8 (1), 1-14

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Quiroz, C. Y., Bustos, J. M., Juárez, M., Bolivar, E. & García, C. (2020). Exploratory factorial structural model of the perception of mobility in bikeways. Propòsitos y Representaciones, 8 (1), 1-14

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Rincon, R. M., Quiroz, C. Y., Espinoza, F. & Garcia, C. (2021). Contrast of a model revision of the entrepreneurship in the Covid-19 era. Journal of Chemical & Pharmaceutical Science, 1 (2), 20-25

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Salvatore, K. (2020). Habitus mobility in the transport of zero carbon dioxide emission into the atmosphere. International Journal of Advances Engineering Research & Science, 7 (2), 1-4

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Sanchez, A., Espinoza, F. & Garcia, C. (2022). Profusión y conectividad del emprendimiento caficultor en la era Covid-19. Vision Gerencial, 21 (1), 1-8

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Sandoval, F. R., Molina, H. D. & Garcia, C. (2021). Metanalytical network retrospective of public transport and its effects of the governance health. International Journal Advances in Social Science, 9 (1), 8-18

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - Sapiro, G. (2019). Rethinking the concept of autonomy for the sociology of symbolic goods. Biens Symboliques, 4 (1), 1-51

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar